Olaf Schlote, born in Bremen in 1961, is a freelance artist.

In his works, he examines fundamental questions, issues from life till death, often journeys with manifold artistic forms that invite the viewer to travel with him. He is interested in the flow of life; of people; of nature, particularly trees and roots. He works his way through the fixation of a photograph in order to pave the way for a transition to a space beyond. He is guided by his inner belief that life is always moving and changing and never static. It is precisely this movement that he depicts in his photographs.

The current exhibition at the Willy Brandt House is a reopening and expansion of the Memories project from 2020.

It is a profound and highly emotional journey to the darkest places in German history, including Auschwitz, Majdanek, Stutthof. He also travelled to Israel to meet first-generation Holocaust survivors - all Europeans - and their descendents. These encounters have resulted in deeply moving friendships marked by a profound sincerity. His encounters with these people and his high regard of the incredible achievements in their lives inspired Olaf Schlote to create lighter, transcendental pictures beyond all abysses. The images were taken by the sea in Haifa, for example. It is to be hoped that the exhibition will ellicit from visitors the same intense and authentic experiences as it did in its subjects. It is intended to create a powerful and, at the same time, fragile alternative concept to emerging present anti-Semitism, right-wing populism and xenophobia, all of which pose unprecedented challenges for today’s society, especially in the wake of the tragic events of 7 October 2023, with Hamas’ attack on Israel and the subsequent escalation of violence.

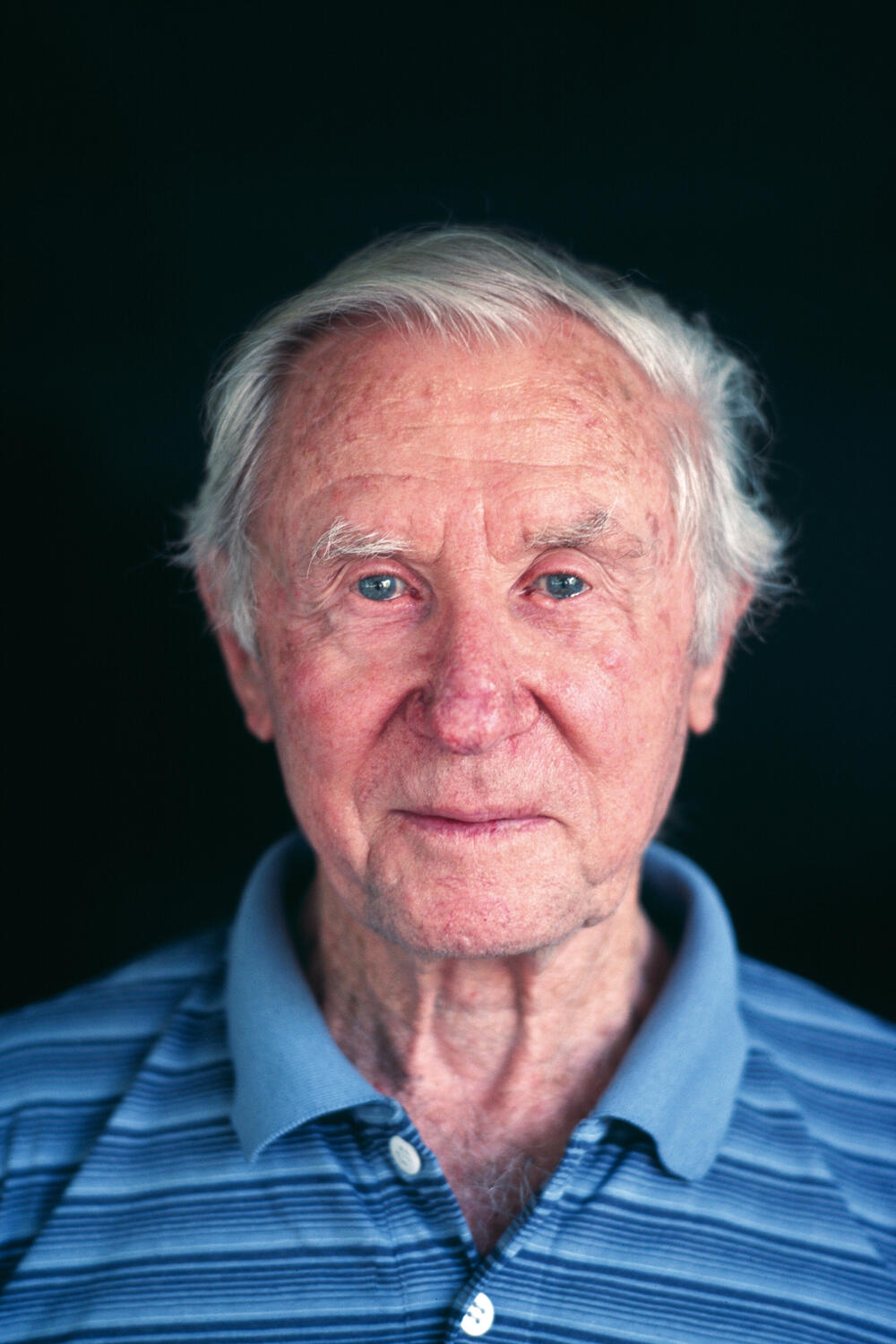

Moshe Zimmermann, born 1943 in Jerusalem, is Professor emeritus for German History. 1986-2012 Director of the Richard-Koebner-Center for German History at the Hebrew University, Jerusalem; Visiting Professor in Heidelberg, Mainz, Princeton (USA), Köln, Halle, München, Saarbrücken, Kassel, Göttingen and Krakow (Poland); Academic Prizes: Humboldt-Forschungspreis 1993, Jacob- und Wilhelm-Grimm-Prize of the DAAD 1997; Dr. Lukas Prize of the Uni Tübingen 2002 and the Lessing-Prize of the Lessing Akademie Wolfenbüttel 2006; Author of many publications in German, English and Hebrew about nationalism, antisemitism, the history of sport, film-history and German-Jewish history, as well as about the Holocaust, collective memory in Germany and Israel, and German-Israeli relations. Involved with the curriculum planning of the Ministry of education.

Wilhelm Marr - The Patriarch of Antisemitism, New York 1986;

Die deutschen Juden 1914-1945, München 1997;

Deutsch,-Jüdisch, München 2000;

German Past- Israeli memory, Tel Aviv 2002 [hebr.];

Deutsch-jüdische Vergangenheit: Judenfeindschaft als Herausforderung, Paderborn 2005.

Die Angst vor dem Frieden - Israels Dilemma. Berlin 2010

(with E.Conze, N.Frei & P. Hayes) Das Amt und seine Vergangenheit - deutsche Diplomaten im Dritten Reich und in der Bundesrepublik München 2010

Vom Rhein an den Jordan. Goettingen 2016

(with Lorenz Peiffer) Emanuel Schaffer - zwischen Fußball und Geschichtspolitik Göttingen 2021

Germans against Germans. The fate of the Jews 1938-1945 Indiana 2022

(with Moshe Zuckermann) Denk Ich an Deutschland. Ein Dialog in Israel Fraunkfurt 2023

Niemals Frieden? Israel am Scheideweg Berlin 2024

When were you born, Mr Zimmermann?

December 25th, 1943 – Christmas Day 1943 …

A lovely date.

It wouldn’t ordinarily have been important to us since Christmas isn’t a special day in Judaism, but at that time, the English were still in Palestine. My mother used to tell me that she remembered that day not only because it’s the day I was born but also because it was the day they lifted the curfew. In practical terms, it marked the end of the war in Palestine.

Your parents are from Hamburg. Your mother’s family had lived there for 400 years.

Yes, the Hekscher family was well-known in Hamburg. Their ancestors had come there from Portugal, seeking asylum. First, the Jews were expelled from Spain, then, a century later, from Portugal. Part of the family went to the Ottoman Empire and another to Northern Europe. My family arrived in Hamburg via Amsterdam and North Germany.

And was your father born in Hamburg?

Yes, his family came from a completely different part of the continent. They were “Eastern European Jews”. His grandfather was from Rava-Ruska, his grandmother from Cherniche – which, at that time, was part of the Austrian or Hapsburg Empire. They emigrated to Germany before WWI, so my father was born in Germany. They lived in Hamburg in a neighbourhood where the poor Jewish people lived, unlike my mother’s family, who were wealthy.

And where was that?

In the south of Hamburg, Hammerbrook, Süderstraße 95. My mother lived where the majority of Jews lived, in Bornstraße in the Rotherbaum quarter. Not far from there was the Bornplatz Synagogue, which was “their” Temple.

And your parents emigrated to Palestine in 1937/1938 under pressure from the Nazis and the societal circumstances?

After 1933, they had to make a decision. Initially, they stayed in Germany but came to realise that the University no longer held any opportunities or prospects for them. In 1937, my mother emigrated to Palestine via England, and my father followed a year later, in 1938. He left from Bremerhaven direct to Tel Aviv.

Did your parents ever talk about what it was like for them when they arrived in Palestine?

They had to give up their home. It was only later that I understood how deep that goes. You’re a Hamburger through and through and have to leave your home city. Palestine was completely alien to them: my mother grew up in a Zionist family, so it was easier for her to reconcile herself to it. But my father was from a working-class, left-leaning family and found it more challenging to adapt. However, he had learned Hebrew at a Jewish teacher training college in Germany, so he didn’t have to learn the language upon arriving in Palestine. That, however, created conflict: on the one hand, it was easier to integrate, especially in the part of the population that was also “Jeckish” or “Yekkes” – that was the name for the German Jews. On the other hand, one always had images of one’s old home in one’s mind. Even I could feel how large this presence loomed in our family: the first time I came to Hamburg I was 32, but everything felt familiar to me from the stories my family had told.

It must have been a huge change, also in terms of the culture. Looking at their first homes there in comparison to Hamburg, and then the change in climate. It must have been an enormous adjustment.

They never complained about that. They adapted, and they were happy to have found an apartment and jobs in Jerusalem—my father as a teacher, my mother as a lab technician. After 1945, they knew just how lucky they had been to have left Germany in time. When you find out who stayed and ended up in Auschwitz, it’s easier to come to terms with having to live in the “wild Orient.”

Were your grandparents killed?

No, my mother’s parents emigrated to Palestine before her. They were Zionists, my grandmother more reluctantly, my grandfather very consciously; he was keenly aware of what it was all about. My grandfather on my father’s side died in Germany in 1937. While it was extremely challenging for him to remain in Germany, he didn’t want to leave. His wife, my grandmother, managed to leave Germany in September 1939 – at the very last minute.

Where are your roots? Do you feel like you have roots in Hamburg, too? Do you have some kind of Hamburg identity?

Had you asked me that when I was twenty, I would have said my roots are clearly in Jerusalem, West Jerusalem, East Jerusalem, in the direct vicinity of King George Street 26. That was my home. Nevertheless, as children, we felt that the Hamburg past always played a role. As I explained, we already had the topography of Hamburg in our heads. We were familiar with all of the habits and customs of the old Jews in Hamburg. But when I came there as a PhD student, I noticed more and more of Hamburg and the German roots in my behaviour. Today, I would say that Hamburg is as much my home as Jerusalem is, even if only because Jerusalem has become foreign to me; it has become too orthodox. The city has changed a great deal since 1967 while I have become ever more familiar with the history of Hamburg, which allowed me to discover my roots here for myself. We’re currently sitting here in Berlin, and I realise that I also have roots in Berlin. I read Erich Kästner in Hebrew; “Emil and the Detectives” is set in this very street.

That has always been one of my favourite books, too!

Well, then, you know exactly what happens. Kaiserallee, which is now called Bundesallee, Trautenaustraße, there’s Nikolsburger Platz, just around the corner from where Kästner once lived, and the longer I stay here, the more I feel that these roots also play a role. The first stories I knew were set in Berlin, which is why the city is familiar to me. This puts the concept of home into perspective. I don’t know whether this would be accepted in Germany in the way that I feel or imagine it. But from my point of view, this shows that you can discover and have roots anywhere.

Yes, the term „Heimat“ can be problematic. For us in Germany, for me, for the descendants of the perpetrators, it’s problematic. We live in a vacuum when it comes to healthy national identity. That’s a separate issue that we should talk more about another time.

‘There’s the 1938 film ‘Heimat’ starring Zarah Leander, or the TV series, ‘Heimat: A Chronicle of Germany’. This illustrates how problematic the term is.

And now there’s another European Football Cup in Germany; looking back to the World Cup in 2006, that was really the first time that we saw people celebrating in the streets, waving German flags and wearing national emblems …

… and being allowed to celebrate in that way …

It’s such a vast topic that we should talk about it another time. Now, let’s turn to the “German virtues”—which aspects of your personality are particularly “German” or even “Hanseatic”?

My mother would have been better able to answer that. She was very typically German. Punctuality, cleanliness, diligence. She embodied everything that it stands for. She would have said: My parenting failed; my son didn’t turn out the way I had hoped …

… You’re the oldest child …

I’m the oldest. I’m closest to my parents. I went on to learn German and of my siblings am most familiar with Germany. But I’m too much of a “Tzabar”, a Jew born in Israel. A bit untidy, a bit “chuzpedik”, that’s what they call it, but I know, in principle, how one ought to behave – in theory at least.

(laughs) That sounds good.

For example, right now, I’m sitting here at the table all relaxed and casual. If I were sitting opposite my grandmother, I would have had to sit up nice and straight …

Let’s go back to this change from Hamburg to Palestine. The hugely different language, the people, the culture, the climate – what influence did that have on your life or your development or that of your siblings?

It’s always a balancing act. You constantly have the past at the back of your mind and try to bring a bit of it into this new reality. That means you’re not living somewhere completely foreign. There’s a bit of Germany in Jerusalem, too. The German Jews, the Hamburg Jews among them, create an environment that upholds what they brought with them to Palestine. That helped them to deal with the situation. I don’t remember them particularly complaining about the climate – after all, it has many advantages: it doesn’t rain in the summer, and you don’t have to take an umbrella every time you leave the house. For Hamburgers, the sea’s never far away. If you live in Tel Aviv, you can always easily reach the sea. So there’s always some kind of compensation. I never heard complaints along the lines of: “Oh no, we had to leave Hamburg, and we want to go back.”

They sound like good parents.

From my perspective, my parents were good people. My mother was a very gentle person, and my father was stricter simply because he was an Eastern European Jew who grew up in Hamburg. He was a school principal, which necessitated a certain degree of authority. But my siblings and I had a very good relationship with our parents and fond memories of them.

Looking at Germany nowadays, what’s the first thing that strikes you?

First, the language. People on the street speak the language my grandmother spoke, which I didn’t understand at the time.

If I understood correctly, you weren’t allowed to learn German initially and later taught yourself.

My parents had decided that the children born in Israel should speak Hebrew. We spoke Hebrew at home, and my parents also spoke Hebrew to one another. They consciously avoided the German language. One of our neighbours, also a “Jecke”, spoke German at home. In our family, there was a clear separation. Until we went to school, Hebrew was the only language we grew up speaking. German only came when I was a student.

Looking at German society and politics in Germany from Israel: what’s your assessment of the situation?

There’s a development. For one, for me, it was always important to see how different German society is nowadays compared to German society before 1945. That filled me with optimism, not only for German society – German society learned from the past –but also for us. If the Germans were able to take a path from the reality prior to 1945 to what we experience today, then we could do the same in Israel and in the region surrounding Israel. These days, I’m more sceptical. When I see how right-wing populism is spreading in Germany, I wonder how long this process will persist. Will there be a real turning point, or is it just a cosmetic flaw? But that’s what I think about when confronted with German society.

And your view of Israeli society?

One always has to view it comparatively. When you see how differently German society behaves with respect to certain topics—how, for example, a militaristic society has become a more pacifist one—and then one looks at Israel and wonders: Why are we so stuck in warmongering? Fighting, war, as the only way to survive. Then, you not only have to deal with Israeli or Jewish history but also with German-Jewish history. And that is what I do for a profession.

The first time I was in Israel, I met photographers Pesi Girsch, whom you might know, and Vardi Kahana, who you might have heard of. Before I talked with them, I was incredibly nervous. I would think: “Oh God, I’ll need to see and be really careful.” But after we had spoken, I felt like, if we wanted to, we could hop aboard that rowing boat and would be heading in exactly the same direction. We are so much more connected than it seems from the outside. Would you say that too?

Wholeheartedly! The first time my mother returned to Hamburg in 1984, around 45 years after she left Germany, I was struck by the fact that she looked exactly the same as other women her age. She left Hamburg as a young woman, and yet she looked and behaved exactly the same as the other women in Hamburg. It became especially apparent when we met up with friends: We spoke the same language – not only in technical terms but also with the same dialect, the same mindset, and the same attitude. While these people left Germany, they remained in the Germany of the Weimar Republic. That’s why there’s still this closeness. And if we look back specifically at life after 1945, it’s even easier to demonstrate or generate that closeness. The specific burden of having lived under National Socialist rule can lead to alienation but can be overcome if one either understands or excludes those twelve years. For our generation, the post-war generation, it’s even easier with our own “uncontaminated” tradition.

Do you still believe in a vision for Israel, in peace?

I have a vision, though I try not to present it as a vision but rather as a solution to a problem. The problem is that Israel and the Palestinians have been embroiled in conflict for a century and are unable to find a way out. In my opinion, there isn’t a vision but a solution. And there is the two-state solution offered by the UN in 1947 – which should continue to be upheld. That’s the solution and, if you like, also the vision. The next question is always: Is that realistic or achievable? It doesn’t appear realistic because the conflict has continued to escalate. But if one were to establish a phase of quiet, at least temporarily, it would be possible to assess the situation, make new plans, and then implement them.

Probably with a different government.

Definitely. It will not be possible with the current Israeli government. It’s the worst imaginable government. While I won’t say anything here that could be used against me at a later date, this isn’t feasible with the current far-right government. It’s a catastrophe for the state of Israel and its people. They’ve got to go. On the other hand, we need to find dialogue partners who are prepared not to fight Israel but to acknowledge Israel as a partner. If that succeeds, the “vision” can be realised.

You recently wrote this wonderful book “Niemals Frieden? Israel am Scheideweg” (Never Peace? Israel at the Crossroads), an intelligent and incredibly clever book, highly entertaining in a way. I’m so thankful for this book because I, too, had to smile at times because the wording is so beautiful, slightly colloquial. And what struck me is that in my conversations with the Holocaust survivors whom I met in 2019, I would always ask at the end what their wishes are for their lives, what they hope for for their children and grandchildren. What’s astonishing is that they all said: for there to be peace and stillness, that all is quiet. How is it for you?

It shouldn’t be used only as a kind of slogan. That’s always the answer one gets: we want peace. But what one always has to ask is what kind of peace? What’s your idea of peace? A graveyard is peaceful. Especially for those who grew up after 1945, one knows how important it is to avoid war, how important it is to seek out alternatives and to live together in peace. The fact that today, 75 years after the founding of the state of Israel, we still haven’t found a way to create peace makes this answer easier on the one hand: Of course, we want peace. But on the other hand, the question is: Why haven’t you been able to achieve this goal? And that’s not only down to Israeli politicians, the idea of Zionism; it’s not solely the fault of the Palestinians, the Arabs, or the opponents of Israel that this hasn’t been possible. I get exasperated when I’m asked this question because, for a long time, I advocated for ways out that were not considered.

You are a very diligent and committed peace activist and always looking for new ways of communicating. For example, in your latest work, you try to explain the background and structures of Israel here in Germany and take a differentiated view. Above all, you advocate always keeping the lines of communication open and continuing to seek dialogue. This is an enormous undertaking on your part.

Thank you for the compliments, but I’m a historian and I try to learn from history. I claim to be able, by comparing society today and in the past, in Israel and in Germany, to reach rational conclusions. I try to present the things I consider to be lessons from history in the hope that this may, one day, provide fruitful, without being under the illusion that we historians can change the world. But simply giving up, sitting back and ignoring the problems would be a betrayal of my profession and my existence as a conscientious Israeli historian.

In my opinion, you are an important ambassador in both directions; you’re someone who builds bridges.

You can put it that way or put it another way: Because I know both societies relatively well, I am able to present each society to the other and to highlight the prevailing problems. That is the advantage.

Mr Zimmermann, many thanks for speaking with me.

Bluma Shindelheim (née Schildkraut) was four years old when the Nazis invaded Demblin (Dęblin) in Poland by the end of 1939 and bombed the city in which she was born. She remembers nothing from the days before the war, but her nights are filled with dreams of fear and terror. Nightmares haunt her and give her no respite. Although it is very painful to recall her past, Bluma insists on telling us her whole story and refuses to skip any description or detail. She struggles to reconstruct every instant of horror exactly as she remembers it, to recreate a patchwork of those terrifying moments that she has never mentioned to anyone.

Bluma was the youngest of four children. Her family anticipated what was expecting them, after young people were sent to labor camps and older people to extermination camps. “My mother stood away from the line and hid me under her heavy coat”, says Bluma. As they were being marched to the unknown, they heard non-Jews shouting and trying to warn them that “There is no way back from there”. One Polish woman yelled at her mother, and told her to dump her little daughter to save her life. Bluma’s mother did so, but because of Bluma’s persistent and desperate crying, her mother went back to pick her. They both managed to run away and hide in the fields, and thus escaped being loaded into the Treblinka train.

They managed to reach the Demblin labor camp, where they joined her father, brother and two sisters. “My mother found a man who was willing to let us get inside the labor camp in exchange for the heavy fur coat she had been wearing.” Her mother gained access to the labor camp, but naked little Bluma was dumped on a pile of corpses at the entrance to the camp. Thanks to her mother’s tenacity and boldness, the child was retrieved and taken into hiding in the camp.

When the Demblin camp was destroyed in 1944, they were transported to a labor camp near Czestochova where ammunition and arms were being produced. Bluma’s father and brother were sent to the Buchenwald camp, and only her brother survived. According to Bluma, the Nazis murdered most of the little children in the camps, by giving them “candy”. This was not “innocent” candy, it killed the children. “My mother warned me not to accept any “candy”, so I just put it in my pocket”. Once again, Bluma escaped death.

Bluma’s childhood is filled with images of horror, violence, cruelty, flogging, and beatings endured by her mother in front of her, a young innocent toddler. To escape these scenes, she ran away and hid in the trenches, playing with her head lice. “I was non-existent, I was not a human being”.

The moment the war ended was documented in a small picture taken in 1946, when she was 9 years old, and they were staying at the DP camp in Germany. Little Bluma was photographed next to US President Dwight David Eisenhower. Bluma and her mother arrived at the Ansbach Nüremberg camp and lived there for about three years after the war ended. Bluma refused to attend a German school and in fact, did not get any schooling at all. One day, there was a knock on the door. When Bluma opened, a child was standing in front of her. “There is a boy here, a beggar”, she told her mother. When her mother reached the door, she was taken aback: “It’s your brother”, she replied.

The family sailed to Israel on the Kedma ship in 1948. Bluma quickly settled in the country, she learned Hebrew, but until she reached sixth grade, she kept transferring every two months to a different school.

Her special connection and relationship with her mother never ceased. “Until I reached age 17 and went into the military, I would sleep on my mother’s feet, I was afraid she would run away from me”, she explains.

At age 19, Bluma married her husband Israel. She opened a clothing store called “Hamsin” in Haifa, where she worked from morning to sunset. Her love of art, culture and literature was obvious to all from an early age. “When I was little, I dreamed of becoming a writer”, she tells us. Even today at the age of 83, she is energetic and active, takes long walks, and listens to music. A quick glance at the book lying at her bedside reveals to us that she is currently reading the autobiography of former US President Barack Obama.

As a fashion enthusiast and the owner of a successful clothing store in Haifa, with the best merchandise from Israel and abroad, it is clear that style, chic and grooming are part of her lifestyle. Today, she is dressed in purple, wearing an elegant shirt and purple pants; with her fashionable curls, she looks decades younger. Her husband passed away a few years ago, yet together they raised a beautiful, exemplary family. She has three children and eight grandchildren. “My wish is to live to see my great-grandchildren, too”, she says with a smile.

When I ask her what else she would like to wish for, she simply replies: “I want to be here forever, I have always been a woman of valor”. Another one of Bluma’s wishes is to travel abroad, to see places and landscapes around the world. Her childhood was ruined indeed, and it is truly impossible to comprehend how such a little girl managed to survive that awful period in history. But then, to some extent, Bluma is still that same little girl, full of optimism and joy of life.

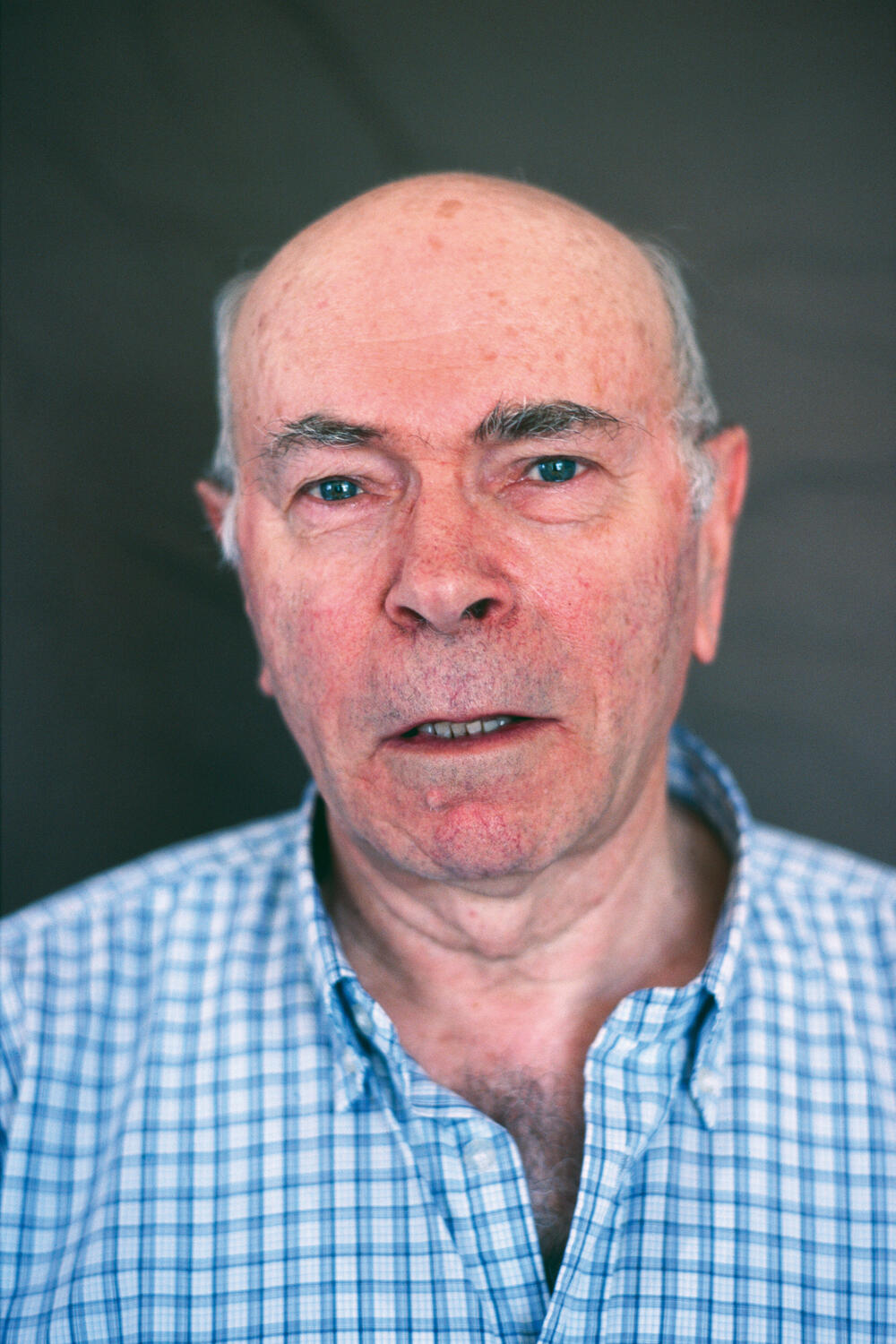

Monia Weisman was born in 1929, in the town of Lipcan, in the Bessarabia region of Romania (now a town in Moldova). There were some 8,000 Jews in Lipcan, which was considered a major town in the area. Monia grew up with his parents, his sister and his grandmother in the same house.

His memories of his parents’ home are mostly related to their simple life in past times: food was stored in ice crates. In winter when the lake was solid frozen, boulders of ice were stored, to be used all year round for food preservation. He remembers his mother going outside, chopping chunks of ice off the blocks. “She would make povidel, plum jam preserves. I still remember the smell of plum jam spreading all over the town”.

In 1940, following the Ribbentrop-Molotov Agreement, the Red Army entered Bessarabia and started to ban and exile the inhabitants. In June 1941, following the German invasion and the opening of the German-Soviet front, the Jews were ordered to pack their belongings and stand in the town square. Thus began the march of death in Transnistria.

Walking conditions were difficult; they walked on foot, with no food or water. They tied their hands together with towels, to make sure they would not be lost. To survive, they would lick dewdrops from plants and leaves. “We ate anything we could snatch from the fields”, he says. The harsh conditions were too much for his grandmother, who could not make it and died on the way. After an endlessly long walk, they crossed the Dniester River, and his mother, too, passed away.

After having marched for a month and a half, they reached the village of Kachin in the Ukraine. Together with another 700 Jews who survived the death march, they were packed into a stable. “We all settled down and slept on horse manure, again without food and water,” he recalls. In these living conditions, illness was common, and they had to deal with people dying every single day. “One morning, we woke up, and Dad was no longer alive”, he says, recalling the moment he became an orphan. “I got sick, with typhoid fever, spent that long winter with my legs folded, lying in that stable. The heat released from the horse manure saved my life.”

Out of the thousands of Jews who were marched to death, Monia and his sister, along with some 80 children, survived the ordeal. They had to resort to endless ways of finding food to stay alive. “My sister would sneak out and bring us sugar beets, and I would walk around the houses in the village and fix shoes with an awning, scissors and wires that I had kept with me since the deportation. In return, I would get food for myself and for my sister.”

They reached the town of Chichelnick and lived there in the ghetto. To get food, he worked for a non-Jew, helping him raise pigs and make pork sausages. Over time, he moved in with the gentile family, who treated him as a son. He remembers the warm affection he received from this man and his wife. He did not get to meet them again after the war.

In 1944, the Romanian authorities gave permission to Transnistrian orphans aged 15 or less to return to Romania. Monia’s sister was 19 at that time, but she looked younger, so they both managed to go back together to Bucharest. Monia found a job in Bucharest and worked as a translator for the Russians. When the Soviet Union forces left Romania, they were sent to the Dombes (?) labor camp in the Ukraine to work in the coal mines.

In 1946, at age 17, Monia boarded the last ship carrying clandestine immigrants, and arrived in Atlit. In 1948, he was one of the founders of Kibbutz Sa’ar, where he was in charge of the farming on the Kibbutz. Since then, he has been living with his wife on the Kibbutz for 72 years.

Looking back at the hardships of his childhood during the war, he comments, looking at the half-full glass: “I decided that I must try to see the good and not the bad. I don’t look back in anger. Family is the most important thing. Watching my family growing, that’s my greatest pleasure”.

Monia has three children, five grandchildren and three great-grandchildren. Some of them live nearby on the Kibbutz. Monia says that each family reunion, every event they celebrate together, brings him great happiness. He has a piece of wisdom for the young generation: “Be optimistic at all times”. He goes on, in conclusion: “There are so many changes that did not exist in my time, from tinkering with cell phones to flying to the moon… Yet, the most important thing is the pursuit of happiness, not riches”.

Leah was born in Grodno, Poland (nowadays Belarus) in 1934. When the Soviet Union invaded Poland, her family was forced to spend the war period in northern Kazakhstan. In the beginning, the family lived in a town called Kazzyk, but later on, they moved to a larger town called Rodnick (in Kazakh: Dzhelombet), a town that had a coal mine and a stone-grinding factory.

Having lived under Soviet rule since she was 6 years old has strongly influenced Leah’s childhood and shaped her life forever.

Life in the middle of the Siberian steppe meant living in the harshest weather conditions one can imagine. Temperatures reached minus 20 degrees; fierce snow storms would change the topography of the place overnight. The snow on the roads was so dense that visibility was non-existent. Each storm would claim its victims: “People lost their way in a storm and froze to death,” she says.

Their clothing was unsuitable for the ruthless weather conditions. During the five years that the family spent in Siberia, they never had the means to purchase new clothing. “Our clothes were infested with lice; every stitch in the garments we wore was bug-ridden. I can’t forget those awful images”. Hunger and lice caused people to be ill, to feel the abdominal pain caused by typhoid fever. “People paid with the price of their lives”, she says sorrowfully. Their main food was bread and it was rationed. Hard workers received a larger portion, women and children were always given the smallest portions.

“Worst of all was the uncertainty, no one knew what the future held; nobody knew what the next day would bear. My parents worried that we would never leave that place, and what would be our fate”. During the war, an expatriate Polish government was formed, and only then were Polish citizens allowed to unite and to establish a school. Leah began attending a school where the teachers were Polish women who did not always have the appropriate education for their job. Belonging to the Polish community, however, gave them a spark of hope that they would be liberated after the war.

When the war came to an end, repatriation began - the return of Polish residents to their homeland. Polish organizations that had the approval of the Russian administration began to organize groups and to get ready to leave. Their departure was not without complications and hardship, and involved the need for a long ride in horse-drawn sleds to reach the train station. Leah and her family boarded freight trains. On the train there were a few Jews who gathered in one wagon. The trip to Poland lasted a month. At the first stop in Poland, passengers reported them to the polish authorities, pointing to the wagon where the Jews were. The wagon was marked, and as soon as the train started moving again, “the wagon was attacked with a hail of stones”.

The family arrived to Szczecin, where they were treated by various organizations. Then they continued to Lodz, where there was a large concentration of Jews. After several months there, they were moved to DP camps, first to Ebensee, that had been previously used as an extermination camp, and then to the Hallein DP camp near Salzburg. Their living conditions improved and, among other things, the Jewish Agency established a Jewish school on the premises.

After two years in the DP camps, Leah’s family arrived in Israel on the ship ‘Kedma’ in 1948. Leah’s brother, who had immigrated to Israel before the other members of the family, was wounded in the War of Independence, a fact that hastened their immigration to Israel. The family came directly to the Ma’abara (transition camp) in Pardes Hanna. However, due to her brother’s injuries, they were given the opportunity to move closer to him - to Haifa. Thanks to her good command of the Hebrew language (acquired in the DP camp), Leah began her studies in high school as early as September 1948. She then continued her studies at the Gordon Academic College of Education. She worked as a senior teacher with preschool children.

The war period was never mentioned or discussed in any way: neither at her parents’ home; not even with her Israeli-born friends; nor later with her husband. That period in their life was simply not mentioned. It seemed that a screen had been pulled down, concealing all their hardships and misery. “There was a complete disregard for that period - it is as if it had never happened, “she explains. Leah began to speak about those days and to tell her story only four years ago, after she joined the “Amcha-Your People” support group.

Lea married in 1953; she has two daughters, five grandchildren and two great-grandchildren. Leah loves Israel with all her might. “Even if I were given the opportunity to live elsewhere and to enjoy all the pleasures of the world - I would not accept it. I am happy to have my home right here, a unique home that provides security, and makes me feel that I belong. And that is matchless”.

In 1941, sensing the imminent danger, Avraam Oster’s parents decided to flee Stanislav, Galicia (Eastern Poland). Avraam’s father tried to persuade the extended family to join them, but they refused. A few weeks later, the Germans invaded the city and killed 30,000 Jews. The remaining 30,000 were kept in ghettos, and by the end of the war, they had all been murdered. Avraam’s father was a member of the Communist party. A special permit from the party was required to get out of town and travel into Russian territory. Avraam’s father obtained such a permit, got a cart and two oxen, and the Oster family― father, mother, five siblings, and unborn Avraam―started their escape journey, on a trip that saved their lives.

Their first stop was the town of Buzuluk (in the southern part of the Ural Mountains in Russia), where Avraam was born. To feed the baby, his mother had to resort to grinding roots that she collected in the fields. Occasionally, she would go to one of the kolkhozes in the surroundings and beg for some milk for him. The family kept moving towards Russia, and every time they reached a new place, they would look for abandoned houses in the hope of finding some food there. On one of these stops, they reached an abandoned sugar refinery. “My mother filtered the sugar from a drainage pipe into a piece of cloth, and fed it to me”, says Avraam.

In one of these villages, they found potatoes in a mice-infested cellar. His mother decided that bringing in some cats would help, but the mice ate the cats. “Using a spoon, my mother would empty the inside of a potato and make some sort of “bowl”. Then, she would fill it with some oil, and add a piece of cloth to make a light”.

From birth to age three, Avraam survived their escape. As a toddler, one of his distant memories from the war is heavy bombings, explosions and terrifying noises. “To this day, he says, I am afraid of the dark and I never use the elevator, I always take the stairs”. Avraam’s family managed to cross the Volga in a barge. When the war ended, the family stayed in several refugee camps, in Czechoslovakia, Poland, and Austria. “We had to wait for five years in the refugee camp in Austria to be allowed to immigrate to Israel. We were given non-Jewish names so that it wouldn’t be obvious that Jews were coming”.

Finally, in 1949, the family arrived in Israel and lived for a while in tents in Natanya. From there, they were directed to the Maabara, the transition camp, in Safed. Life was not easy: the children lived in one hut, the parents in a separate one. There were no toilets or showers. Later on, they moved to a 37-square-meters one-room apartment in the Har Canaan neighborhood in Safed. “There was no electricity, no cooking gas. It would take two hours to warm a cup of milk”, he recalls what life was like in the “new neighborhood” in Safed.

When he was in sixth grade, Avraam quit school, and joined the Work-and-Study youth movement HaNoar Ha’Oved ve-HaLomed. He started picking figs in the fields in daytime, and going to class in the evenings. Later on, when he was called for mandatory military service, Avraam completed just the basic training. He was given an exemption from the full service, but then, he was called back to do active reserve duty in the home front. First, Avraam was an apprentice electrician, and then he worked in construction, progressing to become a building supervisor. He worked at the Israeli National Water Supply Company Mekorot, and took part in the construction of the National Water Carrier of Israel. From there, he went on to work as a warehouse manager at “Rafael” Advanced Defense Systems. “What I couldn’t learn as a child, I learned as a grownup”, he says.

In 1967, he got married and started a family. Avraam has two children and two granddaughters. One granddaughter is an opera singer, the other one is a performer. Avraam tells us that he is extremely proud of his granddaughters. Avraam says he is enjoying a rich and active life. He teaches Thai paper folding crafts at the “Amcha-Your People” support group, and tries to maintain a dynamic everyday routine. He wishes the State of Israel: “Let there be Peace! Enough with wars!”

Miriam was 8 years old when the Germans invaded Iasi in 1940. She remembers how her childhood changed at that moment. She also remembers the change in her family’s life. Her childhood experiences are seared in her memory, a little girl with a big yellow badge that she had to wear around her neck, the fear of unending bombings and the deafening noise that she had to cope with every day.

In 1941, all the Jews were requested to report to the police station to get work permits. “Dad went there and never came back”. That same evening, a pogrom took place at the station, killing 14,000 Jews. Miriam and her mother did not know if her father had survived the atrocity, and the atmosphere at home was oppressing. The family members starved for food. Among many restrictions imposed on Jews, they were forbidden to leave the house before twelve noon, and by that time, there was no bread left in the stores. One day, encouraged by her mother, Miriam decided to leave home early and stand in line for bread at 11:00. She tried to conceal the yellow badge with a scarf she wore, but once she was found out to be Jewish, she was kicked and punched very hard. “It was an awful moment, I know that I was in great pain, but I don’t remember much more”, she admits.

The traumatic experience in the store made her stay at home. The financial situation at home grew worse. To feed themselves, they would clear weeds for a piece of bread. Miriam fell ill and lay in hospital for about three weeks, but no one took care of her. She still remembers a nurse in the hospital gesturing with her hand to signal that Jews should not be checked. “I was sure I was going to die, I shouted for help but no one came”. Miriam managed to be saved thanks to the kindness of a little girl who brought her water and potatoes and thus saved her life.

Miriam went back home. Her mother and sisters spent the following years until the end of the war in the basement of the house. Those were terrible years, full of dread and anxiety about what would happen. “Every time we heard an explosion, we were sure that the house would collapse and we would be buried under all the stones”, she says. Only after the war ended in 1945, she found out that her father was still alive but by then, she had already begun to build a new life of her own. She joined the Hashomer Hatza’ir movement and started to study agriculture. Miriam was also trained as a medic while getting ready to immigrate to Israel. Saying goodbye to her mother was heartbreaking. “We hugged and kissed in the snow, I will never forget that moment,” she says.

Miriam immigrated to Israel in 1948 and settled in Yad Mordechai. The first feeling she remembers from the moment she arrived in Israel is the unbearably hot weather, to which she was not accustomed in Europe. When the War of Independence started, and the situation worsened on the Egyptian border, she moved to a refugee camp in Bnei Brak, started to work in agriculture and to learn Hebrew. Besides Hebrew, she also studied English with a new immigrant from South Africa who recommended studying English literature “so you’ll know English, too”. “Together, we read Oscar Wilde’s writings, Shakespeare, Julius Caesar and that’s how I succeeded in learning the language, “she says proudly.

To provide for oneself at the time the State of Israel had just been created was no easy task. Miriam spent her mornings working in agriculture in Pardes Katz and her evenings studying for her matriculation exam in Tel Aviv. “On my trip to Tel Aviv, I had to decide whether to buy half a pita with falafel, a small chocolate bar, or a handful of peanuts wrapped in newspaper”. Every day she would buy something different, and that would be her meal until dinnertime. After successfully passing her matriculation exams, she joined the IDF in 1950 and served in the first class ever of the Nahal, the Fighting Pioneer Youth groups. She then moved to the Navy, where she met her future husband.

In the 1970s, Miriam and her husband traveled to the US on a diplomatic mission in the framework of his employment at the Ministry of Commerce and Industry. She studied painting, sculpture and drawing. To this day, she is involved in art and painting. Miriam has three children and three grandchildren. “During World War II, I immigrated to Israel and had the privilege of being one of the founders of the State, so I feel I have done my share and contributed”, she says with a smile. Her wish is to reach peace. “We have to keep what we have, and for peace we have to give up something. For peace, it might be worth giving up some pieces of land.”

The story of Chaim Breitman starts two months before the war in the summer of 1939, when his parents realized it was time to flee before it would be too late. Soon after his parents were married, they started towards the border on the northern side of Warsaw, near the town of Bialystok, which at that time, was under Russian occupation. From there, they wandered toward the Ural Mountains, where Chaim was born in July 1940.

After the multiple hardships they encountered on their way, his parents found work in a Russian factory and were mostly busy trying to survive. Chaim learned to speak three languages: Polish, Russian and Yiddish. As a kid, he remembers his parents were mostly concerned with bringing home their livelihood, so little Chaim stayed often with his aunt Zippora or with “Babushkas” who were hired to watch him.

His childhood memories focus on some images that are engraved in his memory. “I remember the sight of my dad gathering potatoes in the basement; the main food we ate consisted of potatoes and bread”, he emphasizes.

In 1946, after the war, the family went back to Poland; nothing was left, no trace remained from what had been theirs before the war. “My parents got threats that if they did not disappear from the village, their fate would be handled accordingly”. Any house or land in the region that had belonged to Jews before the war was taken over by Polish squatters. Chaim’s family was destitute, with nothing left to recover.

The family prepared to immigrate to Israel, and joined the Gordonia group, whose goal was to arrange immigration to Israel.

In 1948, after having wandered for two and a half years in Europe through Poland, Czechoslovakia, Austria and Italy, Chaim, his brother Moshe who was born at the end of the war, and their parents immigrated to Israel.

They arrived in Israel on the ‘Kedma’ ship directly to the port of Haifa. From there, the family traveled north to Safed, where his aunt (his mother’s sister) lived. After a year in Safed, unable to overcome their endless difficulties in finding jobs, his parents decided to move to Haifa. There too, they were met with endless difficulties and yet, the family managed to get by. At some point, says Chaim, they even managed to renovate their home. In October 1955, his little brother Israel was born.

Chaim arrived in Israel when he was eight years old. He had to learn Hebrew in order to integrate into the new society and adjust at school. At the end of 7th grade, just before graduating, Chaim was faced with an important decision, which in retrospect, paved his way in life. Chaim debated between attending the Basmat vocational school in Haifa or the School for Naval Officers in Acre, which at that time was considered the best school in the country.

Tuition was very expensive, a real concern to the family, but Chaim’s father did not hesitate to tell him: “I will see to the tuition money, you just have to make sure you succeed in the admission exams”. The memory of the backing and support he received from his parents brings tears of emotion to his eyes. He successfully passed the exams, and at the age of 15, Chaim began his studies at the Naval Officers’ School in Acre – his life’s dream.

The intense training course lasted five years. At the end, when Chaim graduated, he got a Bagrut maturity certificate, a high school diploma and a third officer grade in the Navy, and became an IDF Navy officer.

Subsequently, he served as deputy commander of a shipyard at the Eilat base in the Navy. His girlfriend Yael (née Yael Levi) served in the same military base. They were married in 1962 and started a family in Haifa. Chaim began working in Kiryat Haplada, the Steel Forge of Israel, and combined his job with his studies in Mechanical Engineering at the Technion, specializing in metallurgy. Chaim admits that his endless motivation came from his parents who were mainly engaged in earning their livelihood and providing for their children’s education. Thanks to his endless motivation, internal discipline and great seriousness, he progressed and succeeded as manager of the smelting plant in Kiryat Haplada. After 35 years of work, he retired.

Chaim and Yael have three children and seven grandchildren. Today at the age of 79, he claims that the most important thing in his eyes is to enjoy life, to watch his health and to protect his family life. For the past five years, Chaim has been going through a difficult time, coping with cancer, which he has managed to overcome and from which he is recovering.

Chaim claims that one more thing would give him great happiness: achieving real peace. “That is really the only thing we need, and if we achieve true peace, everything else will work out just fine”, he says confidently. But he also warns of the times ahead of us: “The world nowadays is in a state of confusion, I am afraid that once again, Israel might be the world’s scapegoat”, he says sincerely.

Zvi was born in Vienna, Austria in 1933. His first childhood memory is also the most momentous moment in his life: Zvi and his sister being separated from his mother at the train station. At that time, he was six, and did not know that the train taking them to his aunt’s in Belgium would determine their fate and save his life.

Kindertransport, “child transport”: that was the name for the operation to save Jewish children and avoid their deportation by sending them to Western European cities. Zvi and his sister Hadassah were saved, but they did not see their mother again. Their mother had paid money to cross the border and was caught. Zvi does not know what her fate was. A year earlier, in 1938, their father was sent to the Dachau concentration camp.

To this day, he remembers the train ride. “We stood in the train wagon; it was very crowded. I held my sister’s hand the whole way”. Zvi and his 12-year-old sister arrived at their aunt’s house in Brussels. When Nazi Germany invaded Belgium in 1940, his aunt and her husband, Zvi and his sister, hid in the attic in their apartment. When they realized that someone had been informing the authorities about their hiding place, the family had to move away and look for shelter elsewhere.

“We were afraid that the Germans were expected to enter Belgium anytime soon, so we started to flee to France”, he recalls the moments of terror he experienced. In the morning, they stopped to rest and one of the family members put on his prayer Tefillin. This caused great alarm among the German soldiers who thought the Tefillin was a sign to English planes where to drop their bombs.

When the Germans occupied France, the family realized that France could never provide a safe haven for them. They returned to Belgium and hid for four years in various hiding places. The railroad tracks nearby were a strategic point for bombing. Towards the end of the war, whenever the Allied bombs were heard, they would run and lay down in the fields to avoid being wounded. Zvi remembers well the moment the war ended: “To this day, I remember a German soldier riding a bicycle and leaving town”.

At the end of the war, Zvi began attending a prestigious school in Brussels. In the fifth grade, he started learning French and Flemish (Dutch). As a youth, he joined the Zionist youth movement, Gordonia. In 1949, Zvi and his aunt immigrated to Israel and arrived in Haifa. His sister had arrived a year earlier. Arriving in Israel was not easy for him and his family, “It was not a piece of cake”, he says honestly.

Zvi began to work as a porter in a radio shop; he learned Hebrew and slowly began to integrate into the new reality. Then he started working for a construction company. In 1962, he met his wife, Zippora. From then on, until he was 80, he worked in a grocery store owned by his uncle and aunt.

Zvi and Zippora have four children and ten grandchildren. At age 86, Zvi says that abundance and progress have definitely changed his lifestyle. “But the thing I wanted to see above all and has not yet happened is peace”. Zvi’s other wish is to see his grandchildren marry. “I want to go on living, I want to start all over again from age 120, “he adds with a smile.

Nona Kahana’s childhood began in an affluent house in Bucharest Romania. Her father owned a large mall and several other shops in the city. As a child, she went with her mother on ski vacations, both in Switzerland and in France. Those trips during her childhood included other sports activities, such as learning to swim and horseback riding.

The good life she had enjoyed so far did not prepare her for the horrible tragedy she experienced at age 7 and a half, when drunk Nazi soldiers roaming the streets of the city shot their guns and killed her mother. “My mother was nine months pregnant. She fell on me and died immediately. I remember screaming,” she says about the moment that changed her life forever. Her father and grandparents were stunned by the loss of her mother. They sat in the living room at the time. “No one came to hug me or kiss me,” she says painfully about the trauma she experienced.

Her father, a widower at 30, soon remarried. Nona’s relationship with her stepmother was not good and her father decided to send Nona to a monastery, where she lived and studied until 1945. Another traumatic experience she remembers is about the rigorous Romanian education and has to do with the punishment she received in fourth grade for not doing her math homework. The punishment imposed on her was to sit on her knees for 5 minutes in a bowl full of walnut husks. “After 2 minutes, I shivered in pain. Since then, I never again forgot to do my homework,” she says.

The invasion of Bucharest by the Russian army changed the ways of life in the city. “They behaved like wild animals, they stole everything. There were soldiers wearing dozens of stolen watches on their arms, all the way to the shoulder,” Nona recalls. When her mother died, Nona promised herself that she would study medicine so she could save people from death. She was 13 when she enrolled in a nursing school, spending her mornings training in a hospital and studying for her high school degree in the evenings. In 1951, her father was arrested on charges that he owned a fortune, but then was released when he paid a ransom. He obtained passports for his family and decided to immigrate to Israel.

The extended Kahana family, Nona, her father, his wife, her parents and their children, came to a one-room apartment in Haifa, where they all lived together - 11 people. When her father went on vacation to Paris, her stepmother decided it was time for Nona to leave home. From then on, Nona had to start life on her own in a new country. She arrived at Haifa’s Pioneer Home, a residence that had been created to help women find affordable housing.

In 1952 she met Albert, also a native of Romania, the two got married and started a family. For 12 years, Nona worked as a nurse at Rambam Hospital. She then went on to work at Bank Hapoalim in various positions, thanks to her wide mastery of languages. Although her career was challenging and fulfilling, she honestly says she regrets not having fulfilled her dream to be a doctor.

Nona and Albert have two children, six grandchildren and two great-grandchildren. At 87, she spends most of her time at home due to the difficulty to move around as easily as she used to. She likes to watch movies while her husband listens to operas; she reads books and he plays on the computer; but they also make sure to have coffee together and enjoy the little moments they share. “The most important thing to me is our health, and to see that we get through day by day”.