Broken Shards

“The sand will remember the waves / But the foam — will not be remembered, / Besides by those who passed / with the late night wind. / From their memory it will never be erased.” — Natan Yonatan, The Sand Will Remember

“Ever since I was a child, death and grief have been my companions.” This statement is almost word for word the first thing Olaf Schlote told me during our initial conversation right after we had exchanged perfunctory pleasantries. He was referring to his memories of the epileptic seizures he suffered in his childhood and to the tragic events of the past that have shaped his life and work. His intimate familiarity with the “twilight zone” of death, which he experienced in every epileptic seizure, has enabled him to stare straight into the eyes of death through the camera’s lens. Just to be clear, there is no gore in these photographs, no pornography of death. His work is a reflection of tragedy, presented through an aesthetic, lyrical and thought-provoking prism.

A window frame lying on the floor, the glass pane shattered into a thousand pieces (Prora 2011, p. 68). One can almost hear the crash. The chaos is contained; nearly nothing has escaped beyond the frame of the window. The meticulous cleanliness of this disaster resonates when one becomes aware of the title of the photograph: Prora — the vacation resort on the island of Rügen on the Baltic Sea, built by the Nazis as part of a project known as KdF (Kraft durch Freude), or Strength through Joy.

There is no joy in the window from Prora. The photograph’s power is that it serves as an echo of that horrific time. Reverberating in the window frame, which appears as if it is struggling to keep all the shards from scattering, is the shattering of human morality, the smashed windows of the Jewish-owned houses and stores on Kristallnacht, and the meticulousness of the Nazi death machine. The horrors did not take place in Prora. Yet, as Roland Barthes sets out in his authoritative essay on photography Camera Lucinda, the photograph “possesses an evidential force, and … its testimony bears not on the object but on time”. Following the heuristic principle, we — the spectators — form a link between the image, the title and time (the sign and the linguistic message). We fill in the story and visualize not just the shattered window, but also the image of a coffin with the smashed remains of millions of lives. For Schlote, “especially the shattered souls of the children”.

Olaf Schlote was born in Germany. His work dealing with the memory of the Holocaust is, for him, an act of assuming responsibility for the deeds of his “ancestors”. It is an obligation he takes upon himself as a member of the German nation guilty of the atrocities committed during World War II. The series of photographs taken in the Nazi concentration and extermination camps, Majdanek (1997, pp. 9—23) and Auschwitz (2019, pp. 37—65), is the evidence of what transpired there. While Schlote endorses the notion of “silent testimony”, the term agitates him precisely because those very buildings, wire fences and trees are present “witnesses”.

Barthes denotes three distinct acts or objectives in relation to a photograph: “to do, to undergo, to look. The Operator is the Photographer. The Spectator is ourselves … And the person or thing photographed is the target, the referent, a kind of little simulacrum, any eidolon emitted by the object, which I should like to call the ‘Spectrum’ of the Photograph.” We will return later to the photographer — Olaf Schlote — but first, we refer to the spectator and the experience of looking at these photographs. These works do not fit within Barthes’ neat tripartite division. The viewing experience is more complex than to do, to undergo, to look. We, in the role of the Barthesian Spectator, comprise those who were there and those who were not. Those who experienced the atrocities of the camps and those who learned about the horrors second hand. Those who survived to tell about it and those who listen to the accounts of the survivors. Those who carry the memories and those trying to preserve them. It is important, in dealing with the Holocaust, to distinguish between the preservation of memory and memories; between the collective and the individual act.

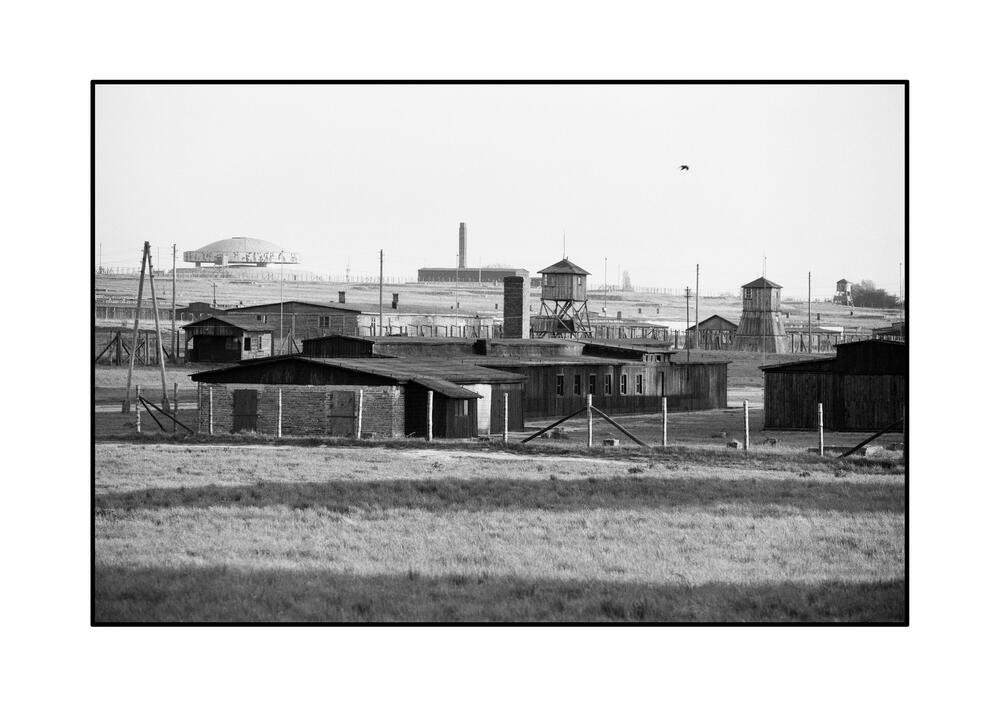

Being Israeli, I was exposed from an early age to an array of photographs from WWII, particularly those related to the Holocaust. The low-slung barracks and looming watchtowers in Schlote’s photograph Majdanek 1997 (p. 10) recalls Barthes’ observation about the immobilization of time in the photograph. He writes, “[the photograph] does not keep it from having an enigmatic point in actuality, a strange stasis, the stasis of an arrest … not only is the Photograph never, in essence, a memory (whose grammatical expression would be the perfect tense, whereas the ense of the Photograph is the aorist), but it actually blocks memory, quickly becomes a counter-memory”. Over-exposure to photographs of this kind has left us — the spectators who have listened to the memories of the survivors, able to “conceive but not perceive,” to quote Barthes. Yet, for the spectator who was once a prisoner in the camps, these photographs unleash a flood of personal, intimate memories: smells of bodies crowded inside barracks, the feeling of bone-chilling cold, the taste of moldy bread they were given to eat. They remember their loved ones who did not survive and their own liberation. Most survivors do not possess any photographs of their families, so while these photographs are not portraits, their powerful imagery constitutes, paradoxically, a kind of “family album” in which the dead are absent-present. The photographs prompt the survivors to remember their loved ones who perished. Looking at the “album” elicits the sharing of memories about a father, mother or sister who was taken away, and others who vanished without a trace.

Memories No. 9 (p. 70) is an especially poignant and disturbing example of the phenomenon of the absent-present. A crumpled coat lies discarded on the ground next to a milestone inscribed with the number 9. A section of steel railroad track and wooden planks slices across the foreground along a sharp diagonal. There is no doubt about the meaning of the railway tracks in the context of the Holocaust. The railway track is one of the attributes of the Holocaust for its role in transporting human cargo to the death camps. The photograph prompts the spectator to think that just a short while ago someone was here, wearing that coat as protection from the rain and the cold. Was he a passenger on the train? Were his clothes taken from him? Was he murdered? There is not a living soul anywhere, just the railway, a discarded coat, a milestone, a number. The associations conjured by absence, anonymity, the number as a substitute for identity, suddenly evoke the numbers tattooed on the arms of the survivors. Or did this number on the milestone bring to Schlote’s mind the date: 9 November 1938 — Kristallnacht?

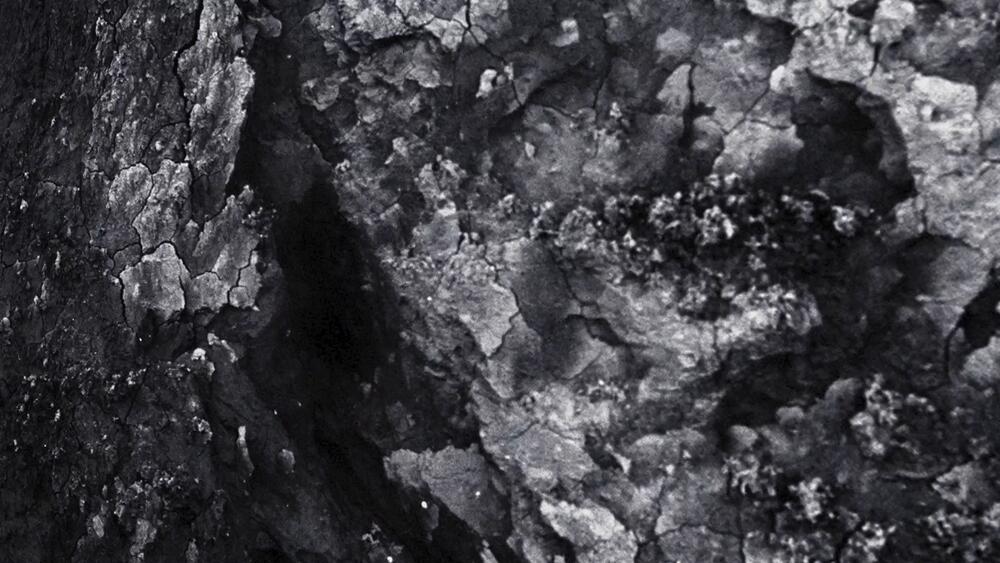

It is precisely these evocative pictures — showing a fleeting moment, part of a building’s interior, an ambiguous or abstract image — that allow the spectator (the survivors and those who have been educated about what happened in the Shoah) to construct a story from the imagery, to give them a context-based interpretation,11 so long as Auschwitz and Majdanek are on their mind. In Majdanek 1997 (p. 15), the rays of light filtering through the wooden slats heighten the dark, gloomy atmosphere redolent of suffocation and despondency. Or do the rays evoke a fleeting feeling of hope? The peeling, moldy wall, resembling a stain in an abstract painting in Auschwitz 2019 (p. 49), summons to mind the ravages of the passing of time, but also a dawning realization of the actual horrors the wall was witness to. This type of imagery is an exception in the visual formula of photographs of the Holocaust. Notably, the photographer Simcha Shirman, a son of Holocaust survivors, whose work also deals with the subject, uses a similar approach in his photographs of brick-wall-as-witness in Auschwitz-Birkenau. According to Shirman, this open-ended image is intended for individual interpretation, since “a single image can serve a multitude of purposes … and mean diverse things to different people.” The disintegrating road in the photograph Untitled, Auschwitz 2019 (p. 55) evokes the idea of the march of weary feet, especially children’s, on that very path to their death. A not-so-silent testimony to the lives that were trampled, it screams: “This happened!” to those who dare deny the Holocaust or its monstrous dimensions.

In an article examining the essence of time and the photographic picture, Israeli art historian Efrat Biberman looked closely at Gerhard Richter’s painting series October 1977 and one painting in particular, Tot (Dead). It is a painting of the head of Ulrike Meinhof after she was removed from the noose on which she was found hanging in her prison cell while awaiting trial. Richter apparently based his painting on a photograph of the deceased. Biberman writes: “When we deal with the photograph of the hanged body after it was taken down we see ‘too much’ in terms of visual information of the horror, and this visual excess creates a pornographic effect of a sight we theoretically should not have seen. The excess of the image focuses our attention on the pornography and eliminates the fact that the image is an impossible one.” In his photographs, Schlote describes the horrendous without resorting to invasive or sensationalist imagery that would result in a “pornographic effect.” He prefers imagery that appears innocuous at first, as for example the photograph Majdanek 1997 (p. 16). The spectator’s attention is drawn initially to the composition’s formal aspects: the play of light and shadow, the strong vertical and diagonal lines, the various rectangular and square shapes at different angles and planes. Pondering this seemingly innocent compositional study slowly gives rise to the shocking realization that the form cutting diagonally across the center is actually a stone slab that had been used for performing atrocious medical experiments on the camp’s inmates.

In Reflection I (pp. 80—81), Schlote again refrains from the straightforward presentation of the familiar Holocaust image — the railway tracks. Here, tracks, light and speed merge into an abstract tempest.15 Schlote’s blurring technique evokes a feeling of distress.16 With the viewpoint left ambiguous, the spectator wonders whether this might be the memory of a person who was on a fast-moving train, being sent to the camps, a view from inside the train looking out of the window at the tracks speeding past? Or are we looking down at this scene from above, from some indefinable place? This image reflects Biberman’s thinking that, “The effect of photographs is in the presence of an impossible moment, a moment torn from the sequence of time or a moment which was never recorded.”

Pondering the essence of photography, what separates it from other types of images, Barthes writes: “What the Photograph reproduces to infinity has occurred only once: the Photograph mechanically repeats what could never be repeated existentially.” What Barthes means is that the photograph captures a fleeting moment, one that can never be repeated in time. Olaf Schlote does not attempt to capture the fleeting moment; he reaches for the eternity of memory. For him, it is the survivors’ personal memories that must be preserved and retold — the story and its moral — so that another genocide will never happen.19 Thus, the exhibition Memories has a double purpose: to save the individual memories of the survivors by conserving them within their personal story, which, in turn, will allow others to safeguard the memory.

The colourful portraits of the eleven survivors form a bridge between the past, present and future, between yesterday and tomorrow. Their cheerful smiles do not reveal anything about the nightmares and agony each of them has experienced in their lifetime. They are the victims, the witnesses, and the conquerors. They are the memory-carriers, and through their personal memories — which will be told over and again — the memory of the atrocities will be preserved: “Today, after having lived in Israel for the past seventy years, [I realize] the importance of telling about the past. In one hundred years from now, no one will believe that the Holocaust happened. How can you believe that a one-year-old baby is burned to death?! It is important to me that this should be written in history and recorded, so that this suffering is never repeated. No one should ever go through these horrors again,” says Gitta Beeri.

During our conversations, Schlote explained his preoccupation with the Holocaust: “Well, it has to do with my roots! [Germany is] … where I was born and taking care of our history with responsibility. ‘Never again’. In a way, I try to transform the deeds of my ancestors into art.” For Schlote, trees are also carriers of memory; metaphorically, they are bridges between the past and the future. The fact that the trees, which still stand in the camps, were witnesses to the barbarism and slaughter, distresses him greatly. He therefore decided to photograph them in all their barrenness and nakedness (p. 62). In the series Reflection I, he opted for total abstraction, using the technique of the close-up to achieve it (pp. 82—83). In another photograph from this series (p. 84), the watchful “eye” of the tree stares back at us, reminiscent of that defiant eye hovering above the carnage in Picasso’s Guernica, which asks of the spectator: How did such an abomination ever happen in our world?

In the epilogue, the colour photographs in the series Reflection II, Schlote tells the story of life after. This is the story of the survivors, of the ones who succeeded in sprouting strong, sturdy branches and new roots, of people who were able carry on and live rich lives — despite the darkness that obscured their past. The abundance of water, exposed roots, are proof that resurrection, renewal is possible. Here too, he uses the technique of blurring to create a powerful, temporal image of a bridge connecting the past and the present, sky and earth, physical and metaphysical (pp. 176—181, 188—189).

Schlote transforms the connection between the photograph and what it represents — the sign and its significance. In one photograph, two red parasols are planted in the sand next to two empty, white plastic chairs on a beach (pp. 201). What might signify to the spectator a pleasant summer vacation instead shows the loneliness and the emptiness that remains despite a life well-lived after the war. The same applies for the images of peeling walls (pp. 192, 195), which stridently echo the photographs of the walls in Auschwitz (pp. 49), as a metaphor for the disintegration of a life lived to its natural end as opposed to a life cut short, crushed and dissolved on purpose!

There is light that burns the time that lives it,

and there is light that erases the time that has not yet lived it; and there is black light that freezes time to a standstill.

— Simcha Shirman, “The Light Remembers”

Memories

Faces gaze at us from vibrantly coloured light boxes; some smiling, others solemn. Altogether, eleven, old, friendly-looking people. They have seen a great deal in their lives. You can sense it in their faces, even though their visages do not disclose what they witnessed. This becomes apparent only when one looks at their portraits alongside Olaf Schlote’s deeply moving series of photographs entitled Memories.

Only then does one become aware of the painful personal stories etched in their faces. These people suffered unimaginable things. Saw those things with their own eyes. Lived them in real life — and survived. It happened to them when they were young. Not everyone who endured the horrors of the German death camps, the dreadfulness of the Shoah that defies description in word or in image, lived to see it end. All who did survive the persecution were forever changed by it, emotionally and physically.

Seeing their animated faces is a completely different experience when you know the context. It becomes more direct, more physical, once you become aware of it. Olaf Schlote’s series provides this context through images that highlight the horrors. Suddenly, the impartiality with which one usually looks at a portrait, whether just glancing at it or studying it in depth, disappears. One’s curiosity about the people in them disappears. I would rather avoid their friendly gazes. Especially since I am, myself, a descendant of the perpetrators of the genocide, of those who made the rules and carried them out or who chose to look the other way. I feel ashamed. I share the inherited burden of history that can never be expunged. The history of my country. My history. I seethe with anger. Anger about the many people who relativize or deny the countless crimes carried out against these friendly people who look at us and against the millions more who were murdered in the death camps. And even more anger that the number of verbal and physical attacks on Jewish people in Germany is rising and that a recent massacre in autumn 2019 only failed to murder the Jews inside a synagogue because of a heavy door that was locked.

The great, forgotten historian and social philosopher Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy, who was the rector of the University of Wroclaw in 1933 when Hitler came to power, and who saved himself by emigrating to the United States, summed up the situation thus while visiting Germany after the war in 1945: Goethe and Schiller, Hitler and Himmler, all are now part of German history — German history is not divisible.

Recently, some never-before-seen photographs of the pogrom of the nights of 9 and 10 November 1938 (Kristallnacht) were circulated on the internet. Disgusting photographs, repulsive in what they showed. They were taken by two photographers from Nürnberg and Fürth. The album containing these photographs was found by a woman named Elisheva Avital among her grandfather’s belongings after he died. He had been a soldier with the Allied Forces in WWII. The photos show members of the German SA (Sturmabteilung), the Nazi paramilitary wing, ransacking Jewish homes and Jewish-owned shops, looting synagogues and carrying off valuable books, pouring gasoline onto the synagogue pews to be set alight, and the charred remnants of the burnt, destroyed synagogues. There are photos of the people whose homes were being plundered. They appear confused and dazed in the face of the pillaging; humiliated at being photographed in their grief and despair. One person has blood running down his face and onto his shirt, his hand covered with a towel; others, apparently awakened from their sleep by the Nazi marauders, are photographed in their pyjamas and bathrobes. The backs of the photographs bear the copyright stamp of the photographers along with the date: “10 Nov 1938”, the same day these atrocities were committed. After the defeat and collapse of the Nazi regime, an overwhelming majority of Germans said they did not know what was going on. Not even when their Jewish fellow citizens had been forced to wear the Star of David on their garments, marking them for eventual deportation to the death camps.

The horrific memories of the people in these portraits are the subject of Olaf Schlote’s photographic series. As soon as we realize who these people are and what they have gone through, we find it difficult to look them in the eye. Prolonged looking at these impressive 40 x 60 centimeter portraits reverses the viewing experience: it is as if they look at us before we look at them, with the result being that they are not the focus of the cycle. Instead, we are the focus. We are addressed by them, but without any criticism or blame. This is an unsettling experience, that the survivors, no matter if they escaped from the death camps or were saved by coincidence and good luck, do not regard us with contempt or censure, but with kindness and benevolence. We are the ones who should never forget what happened to them. Never forget the heinous crimes people committed and are still capable of committing. Especially regular people like us who are now looking at these photos. It is we who must always remember so that we can stamp out even a barely perceptible smouldering fire, prevent another systematic killing like the German extermination camps from happening ever again. The memories of these eleven witnesses must become part of our own and of our descendants’ memories, with the provision — never forget!

Olaf Schlote’s use of backlighting lends the portraits of the survivors of those unspeakable horrors special meaning that is difficult to put into words. Aura might be an appropriate term. In his famous essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, Walter Benjamin, himself a victim of Nazi Germany, defines aura as that “unique phenomenon of a distance however close it may be”. In this sense, Schlote endows these portraits with the lost memory of the religious meaning once held by a picture — that of religious icon. But the reproduction technique employed here also achieves something else: it highlights an opposite effect by empowering the portraits, thereby transforming the personal, subjective experience, as if by osmosis, into a collective, social one.

In the West, the origin myth of the picture is closely linked to remembering. In Historia naturalis, Pliny the Elder tells of the potter Butades, whose daughter, when saying farewell to her lover, carved a silhouette of his face on the wall. The image served to fuel her memory. It represented the absentee in effigy; it was, so to speak, a surrogate for the missing lover. In antiquity, ancestor worship used the form of the portrait so that the deceased will be remembered by following generations and thus was assured of life after death.

Roland Barthes based his phenomenological theory of photography on an old photograph of his mother from when she was a child. Contemplating it, he developed the theory that photography creates a physical connection between the picture and the person looking at it. Something in the photograph — it could be a minor, incidental detail or a gesture — elicits an unexpectedly strong reaction in the spectator. Calling it “punctum”, as if it almost physically punctures the observer, it denotes the personally touching detail that forges the relationship between it or the person in the photograph and the spectator. In Schlote’s portraits, the punctum are the eyes. For Barthes, photography attests to the profound sadness of the unrepeatable, historical moment, what he calls “ça-a-été”, “that-has-been”. When we look at the photographs, it is as if what they imagine happens all over again. Any incentive to remember becomes a bridge to the present.

Schlote’s technique makes the people in the photographs seem both near and far, present and absent at the same time. Dwindling in number, they are among the last who saw, suffered and survived the horrors of the Holocaust; witnesses and victims at once. Schlote regards his “marvellous” light boxes as a kind of “hall of fame”, a rallying cry against forgetting and of championing of the will to survive. Aided by intimate interviews with the people in the photographs conducted by Israeli political scientist and journalist Yael Kishon, Schlote was able to make his pictures of them not only about the past, but also about the burden of their memories. Many pictures are about modern Israel, the country where these people eventually found a home.

Memories is a multimedia-based series utilizing a nearly cinematic method of visualization that incorporates language and images correspondingly. The individual memories of those who underwent the horrors are documented through language, while the images create a universe of memories apt for our visually-based culture. The pictures offer a visual precondition that enables the preservation and passing down to the next generation of the awful memories of the Shoah, which despite their incomprehensibility for us, leave traces of actual experiences at the same time as they demonstrate the inability to portray the horrors in pictures. Even the most hyperrealist art is inadequate to begin to describe the genocide of European Jewry and the cold, calculated reasoning that drove it. It unduly diminishes its dimensions.

In his controversial book Images in Spite of All (2008), art historian Georges Didi-Huberman argues for the representability of the Holocaust in his study of four photographs from Auschwitz Birkenau taken clandestinely by one of the Jewish prisoners in 1944. The photos show women being herded into the gas chambers and the cremation of the corpses. Responding to critics claims of voyeurism, he asserts the importance of the images of the atrocities as evidence, testimony and resistance.

Schlote’s pictures too are “images in spite of all”. Images that do (or are meant to) refer to the material remains of the atrocity and to the handful of survivors. These are, so to speak, meta pictures. These are behind-the-scenes pictures, not illustrations. In order to achieve their full impact, they require the spectator’s imagination. Memories is comprised of single photographs, groups of photographs, a tableau of photographs, and spoken and written words. Through the individual elements and their cross-referencing, Schlote creates a work in which each element is enhanced and endowed with further meaning. The core of the work is the group of eleven portraits of elderly people looking at us, the spectators. A twelfth light box, a tableau of images, serves as an index for that haunting group of works.

The tableau itself comprises twenty black and white photographs of identical size, some vertical, some horizontal, arranged in five rows, one above the other. All of the pictures are from Auschwitz, including the sign at the entrance to the extermination camp bearing the cynical motto “Arbeit macht frei” (work sets you free). There are pictures of the grounds, steeped with the crimes committed on that soil, the remains of the incinerator, the arched lamps that lit up the giant extermination camp at night, the trees that disclose memories in their rings, railway tracks that transported human beings in cattle cars, and debris. Amongst these is a photograph of two barbed-wire fences at right and left that meet at a focal point, thus trapping the spectator, leaving them without any way out. A view from the inside of a room towards the glaring daylight outside is a citation of the most famous of those four photos taken in secret in the extermination camp in August 1944. Probably shot from inside the gas chamber, it showed the burning of the corpses outside. All the photographs in this index become a code that permits only one reading: Shoah.

Next to the portraits and the photo index, Schlote groups photographs of the Majdanek memorial site taken during a visit there in 1997, and free visual associations, some from 2016, of which several were exhibited at the Stutthof memorial site. There is a colour photograph of a burning candle in a light box, a reminder and an appeal to never forget. A gloomy, black and white photo of erosion seems almost abstract, without much nuance. The highlights intensify the physical impact of its massive 100 x 140 cm size. Amongst the images is a single photograph of a view taken from the pitch-black darkness inside towards the outside. Despite the dark and gloomy surroundings, the image seems to offer the spectator a sense of dubious respite. The photographs attest to the time the artist has spent dealing with the devastating legacy of the murderous Nazi regime. The indoor scenes alternating with outdoor views have a mainly documentary feel. Their aim, to create the impression of the camp’s wooden barracks, cramped spaces, barbed wire borders. In an iconic photo, two women are trapped within a triangle constructed from wooden planks.

The types of photography — indexical, iconic, symbolic, black and white, colour, regular format and oversize, their arrangement, and their points in time — prove Schlote to be an artist confident in the medium of photography but also aware of its possibilities and limitations. He is mindful of the difficulty of envisioning the unimaginable in a medium whose very technique is interwoven with visible experiences, but which at the same time, can transform these images into objects of beauty. Schlote thwarts this inclination by constructing a conceptual recollection out of all the different aspects and their pointedly fragmentary portrayal. This recollection continually opens new paths for the imagination that demand the spectator to think about the images while looking at them.

For the most part, photography is considered a medium for the preservation of memories. A photograph preserves memories in a visual form, arresting them so that they become part of an immutable archive. The brain operates differently. Memories are constantly changing during the process of connection making that is going on inside the brain. They remain alive and can be manipulated from outside. Sometimes new connections interfere with the process of remembering. Then, the only thing they share is the occasion or the cause. When the brain has a disorder, some memories become rigid.

Memories conserves the recollections. The series intertwines several layers of the past, positioning them face to face. On one side memories of the extermination camp, on the other, modern life in Israel. The portraits of the eleven survivors connect the distant past, unimaginable for the viewer, with the more familiar, recent past in Israel. Schlote obscures these discrepancies not by repairing them, but by the series’ elliptical structure through which he creates a fragile basis for the spectator’s empathy.

It is no surprise that the pictures from the extermination camps contrast sharply with the later pictures from Israel. The use of colour is the most prominent difference, as the nuances in the precise colour schemes orchestrate the mixing of varied sentiments. The subjects of the contrasting worlds are often the same — the earth, trees with strong roots firmly planted in the ground, walls, doors — but they look very different. The memorial photograph of the lit candle against the dark background and the inscription “For Stutthof” has neither the full impact nor the transparency of the group of four photos of green plants, nor the floating, somewhat blurred atmosphere of the impressionistic image of the beach, or the weight of the photographs of nature or of objects. In the chronological sequence of a gradual but by no means continual extension of the view from inside to outside, from narrow to wide-open space, from depredation to civilisation, a humanly possible future, nevertheless, materializes. Wounds heal like the lesion on the trees in one of the light boxes. In one photograph, the horizontal slats of a door block our view. Light reflects light. Once more, our view is reflected back at us…

Klaus Honnef