Many consider photography a storehouse of memory: this includes historians as well as tourists. Photography is a special kind of storehouse. It preserves memories in a vivid form and, at the same time, it freezes them — unlike the human brain. In the mind, memories change incessantly. They remain alive. At times, memories take on entirely new aspects and come to share only their common point of origin with the things to which they are linked. Only in a diseased brain do isolated memories become fixed and immobile.

Memory deceives — inevitably. That is why some attribute a greater reliability to photography: some even truth. Anyone who still knows how to differentiate between the reality of images and the reality of personal experience knows how true photographic images are. According to aesthetic theory, it is only photography that captures what once stood before the objective of the photographic lens and had already irrevocably sunk into the past as the photographic mechanism was released to capture it.

Olaf Schlote bridges the gap defined by this distinction and dares to attempt a balancing act. He creates something extraordinary in the process. With his photographic project ‘Memories’, he opens up spaces and corridors. He frees ‘fixed’ remembrance from the strictures of categorical attributions — those assigned by both art and science. Memory is able to wander freely and, nonetheless, does not lack orientation — just as in ‘real life’. It is true that photographic images provide orientation in his project; however, they do not suppress the subjective experience. Individual and collective memories interweave, but they still retain their independent character. The collective memories are incorporated into the individual memories. Remembrance literally becomes a corporeal experience.

In order to realise this balancing act, several prerequisites are required: suitable images, on the one hand, and a particular environment on the other. Bremen’s ‘culture church’, the Kulturkirche St. Stephani, offers an appropriate environment: a place of gathering and a place of commemoration. Schlote had already realised one portion of the photographs at an earlier date; the others were created specifically for this project. In addition, every prerequisite has to be linked together in such a way that they correspond with one another: a question of the presentation and staging of images. Accordingly, the character of the place is to find itself reflected in and to resonate with the character of the photos — and the reverse, as well.

For viewers, the encounter with the photos of ‘Memories’ in a place dedicated to commemoration and gathering (in the double sense of gathering one’s thoughts and a gathering of people) becomes an encounter with their own memories as something foreign — and vice versa. This results from the specific arrangement of the photographs, which merge into an ‘installation’. Memories are clearly recalled to mind without simultaneously becoming concrete. This statement sounds somewhat contradictory, but light is shed upon it by the fact that the potential viewers are mentally transformed into visitors to the church as they enter into its space. Here, the images confront them as independent units (entities), as embodiments of memory. In Schlote’s photographs, the process of remembering becomes an element of perception. They show how memory takes place. The process becomes visible, but not representational. Accordingly, it is not a matter of photographs that depict something in the traditional sense but of complex vessels, in which the visible and the non-visible meld into an indivisible unity and are concentrated into an emotional experience. One’s own memories become foreign and foreign memories become one’s own.

The entranceway vividly demonstrates what is meant by this. On one side, there is a row of photographs with distant horizons that emerge in their middle grounds. They invite viewers to let their thoughts wander without limits. The photos opposite them narrowly confine the viewer/visitor’s gaze and show man-made border markers, towers, fences, barbed wire. Together, these positions mark the poles between which life, memory and also the medium of photography take place. Flowing and obstructing, nature and culture, happiness and pain, the curved and the angled, the feminine and the masculine principle, submission and resistance: keywords communicating potential insights. In walking back and forth, in meandering and pausing, the viewers/visitors experience the operation of remembrance in the form of a physical act.

The two parallel, dialectically interrelated but spatially separate, series of photographs suggestively lead towards the sanctuary. ‘Requiem’ is to be found there. Even at a distance, the rays of light emitted by the bright light boxes that serve in its presentation shine clearly. However, before viewers/visitors reach the sanctuary, their attention is drawn to the two aisles of the church. There, what had to this point been experienced at a primarily private and individual, indeed, at a subjective level is expanded to include an objectivising and also societal dimension.

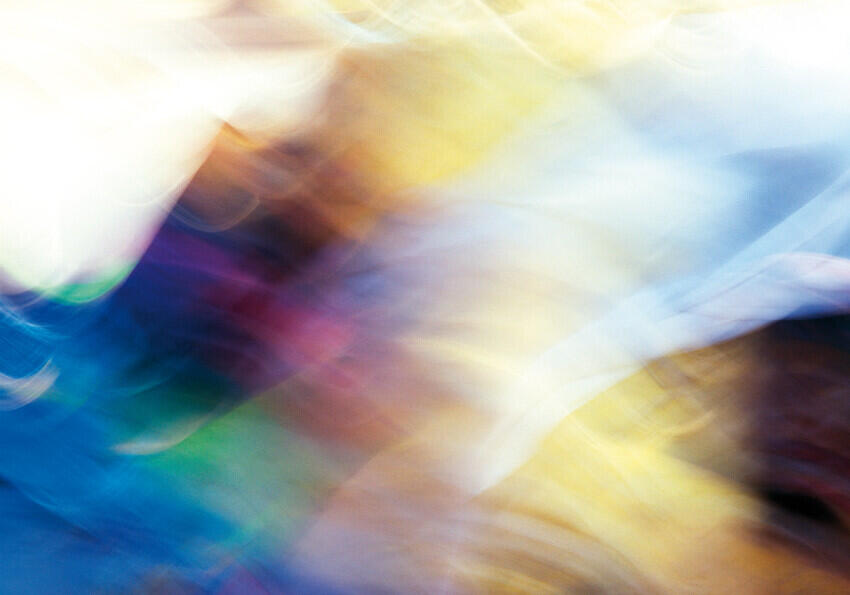

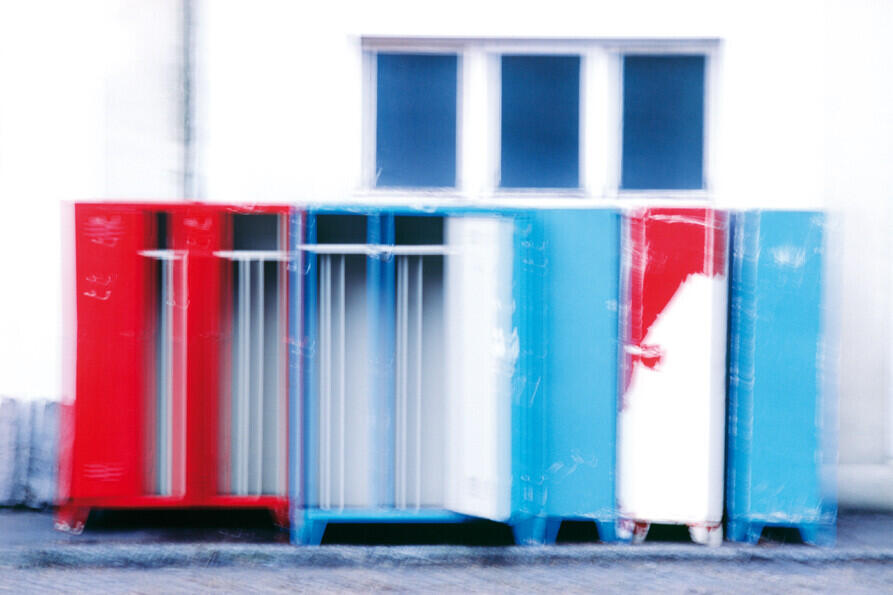

On the left, a precisely composed series of colour photographs offers insight into the specific character of remembrance. Here, in contrast to the series of images already passed through, the formation of memories is realised, so to speak, from an external point of view, as a photographic description. The photographs gathered in this section of the space give concrete form to the diffuse impressions and experiences inspired in the minds of viewers/visitors in the course of the long entrance corridor. In an elliptically composed sequence, they visualise the form — presumably — taken by the path of remembrance: from an indistinct impulse to a gradual concretisation in the process of attaining at least a provisional certainty. On the other hand, the photographs demonstrate the fact that memory and fantasy inevitably intermingle and, also, the manner in which they do so.

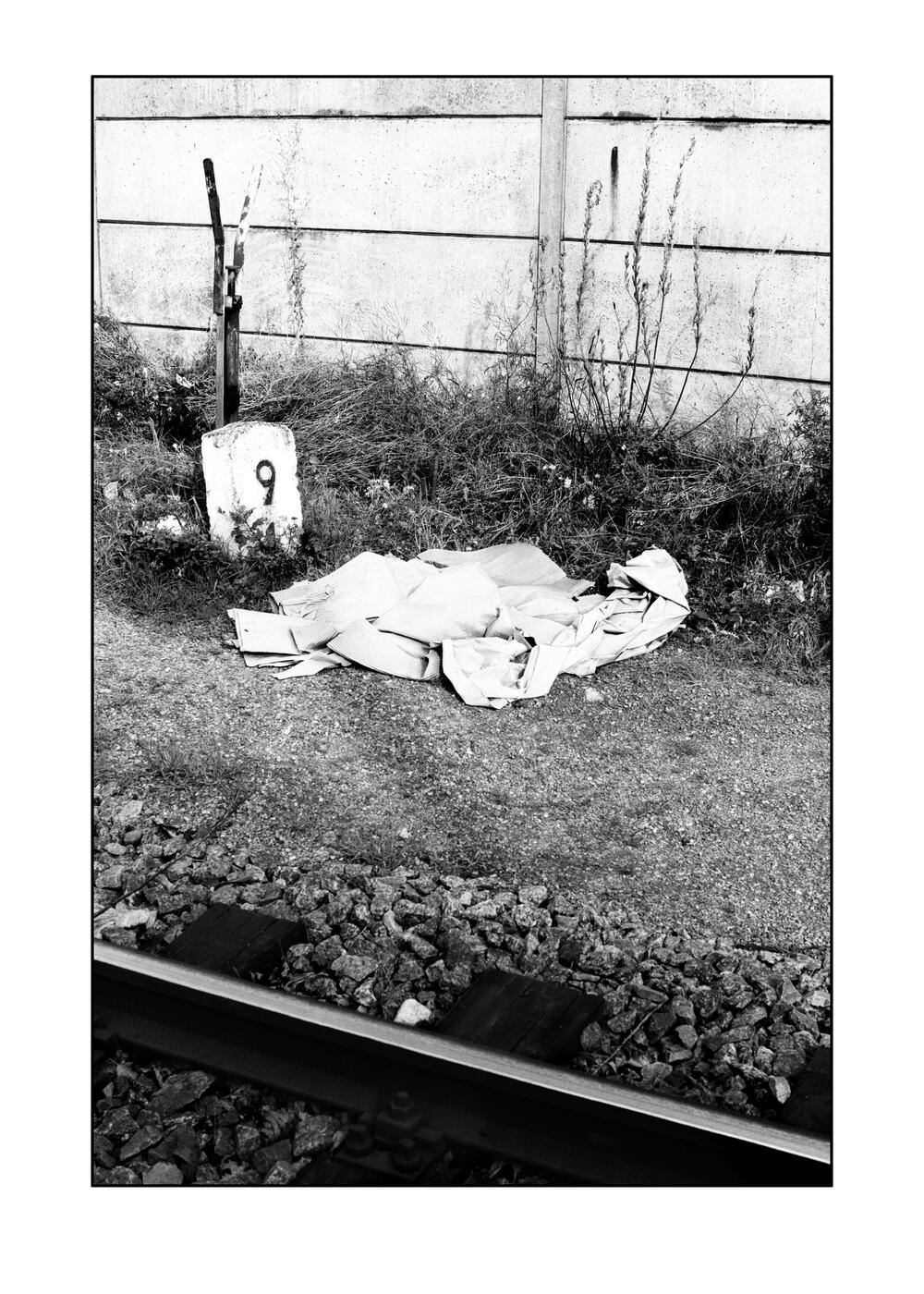

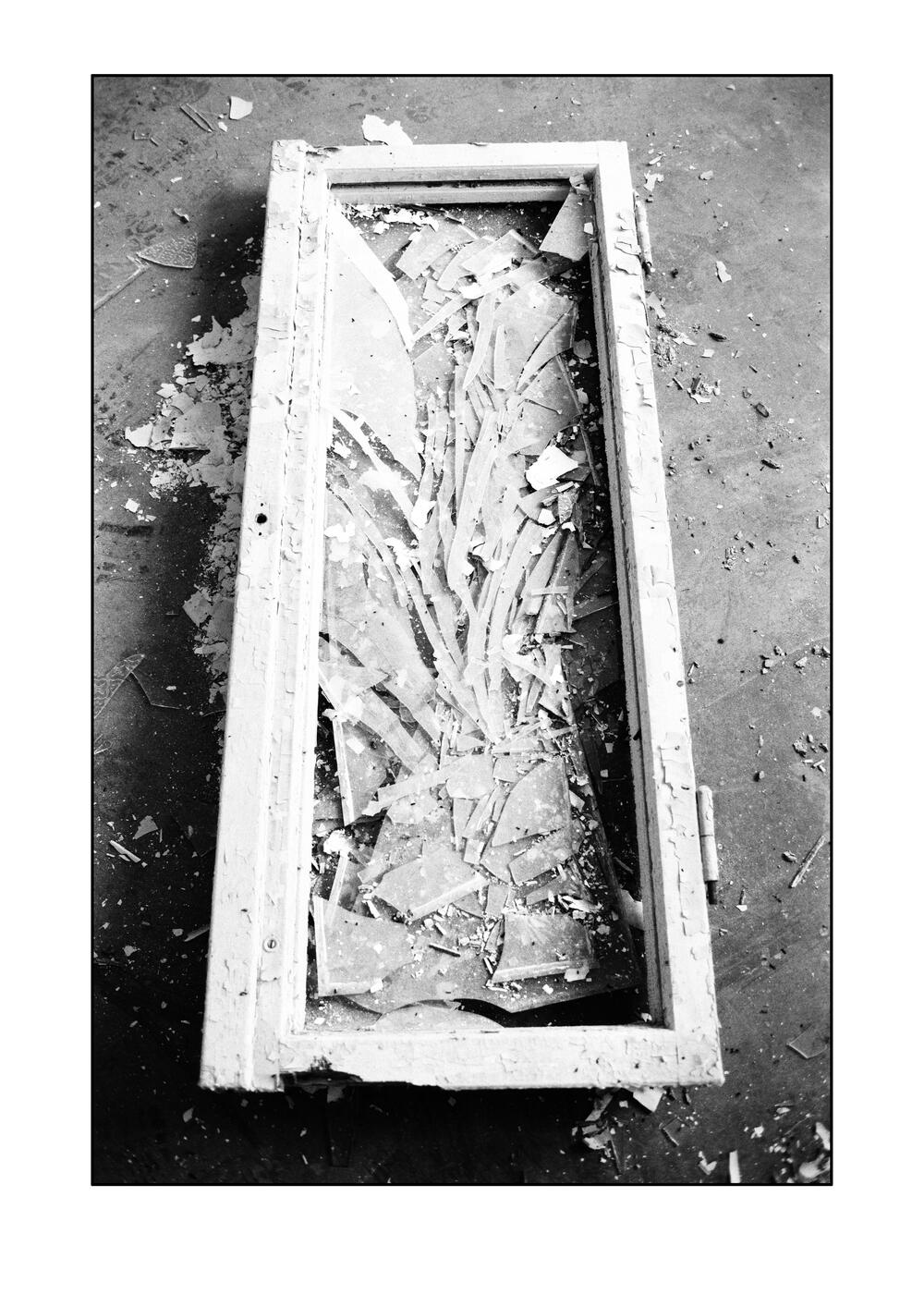

On the right, an unwieldy block of collective memory, in the form of a tableau of highly moving black-and-white photos, emerges from the fog of meandering subjective remembrance — framed in black and thus emphatically contoured. This provides an exemplary fulfilment in the most concrete form possible of what had already been symbolically suggested. Furthermore, it is a thematic complex that is usually repressed, but is, nonetheless, incessantly revived. This block of collective memory weighs particularly on all those within German-speaking culture’s sphere of influence — and no less heavily upon those who have been expelled from it and nonetheless must consider themselves fortunate to have been able to rescue at least their physical bodies. And it will prove a burden to their children and their children’s children. In images like these, the dark side of memory is exposed to concrete scrutiny. However, this is done in an appropriate form, one that transforms the non-visible, the sheer horror that has etched itself into the photographic motifs, into a ‘graphic’ silence — in a form that does not illustrate anything at all, but rather produces that insecurity required to avoid robbing horror of its fearsomeness. What remains are nothing but the monuments that, through their sheer existence, bear witness to what took place within them and that keep its memory alive.

Again and again, Schlote reaches beyond the limits of the visible in order to incorporate the realm of the non-visible into his photographs and to identify it in spite of itself. The photographer’s dilemma is obvious. The half-open door that appears in one image in both the right and the left sections of the space faintly hints at the photographic aporia. What is the significance of this door? Is it opening or closing? In the one case, in the colour version, it can realistically be supposed that it is opening. In the other case — as long as it served its function in the death camp — it definitively closed behind those that had passed through it, definitively!

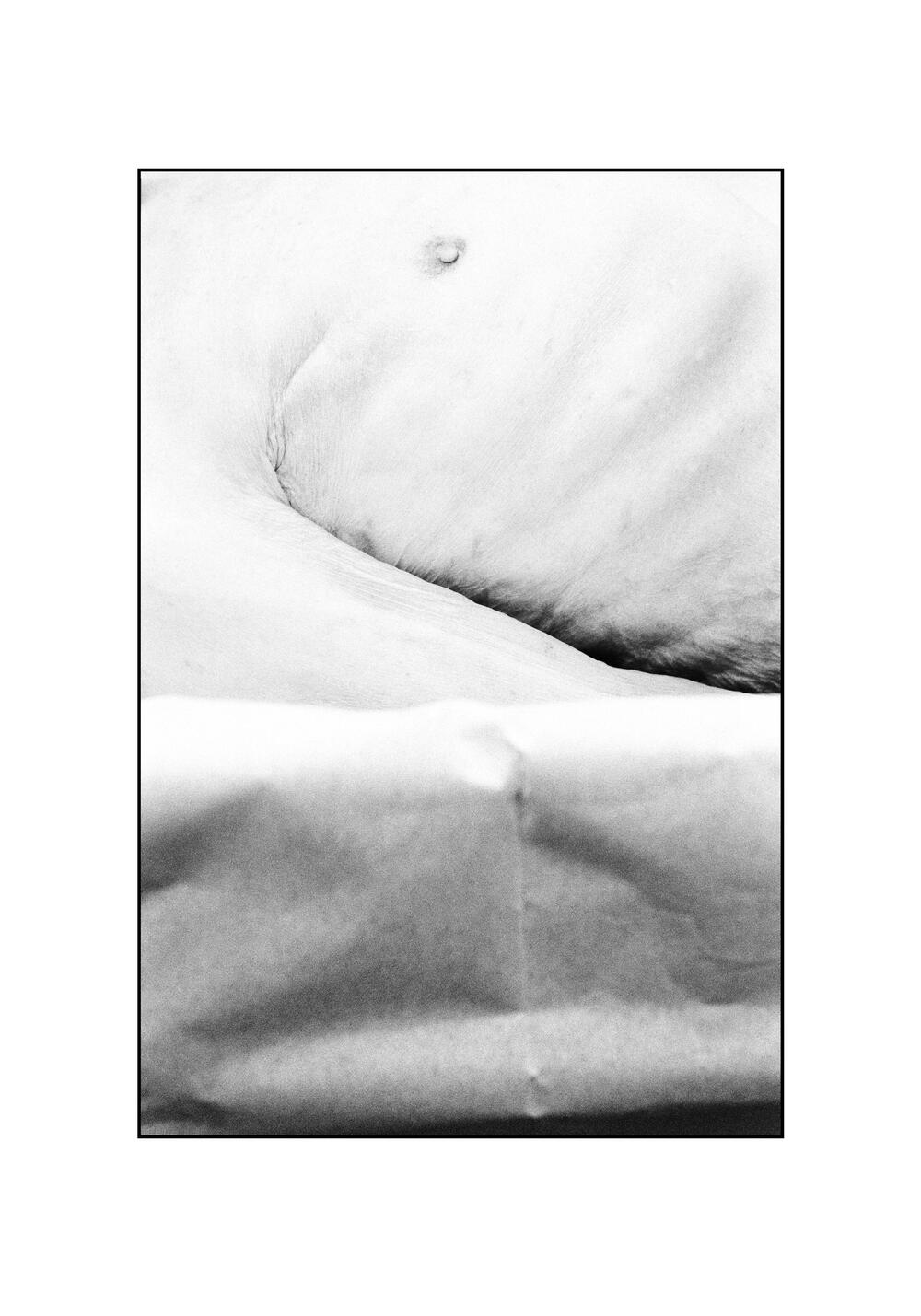

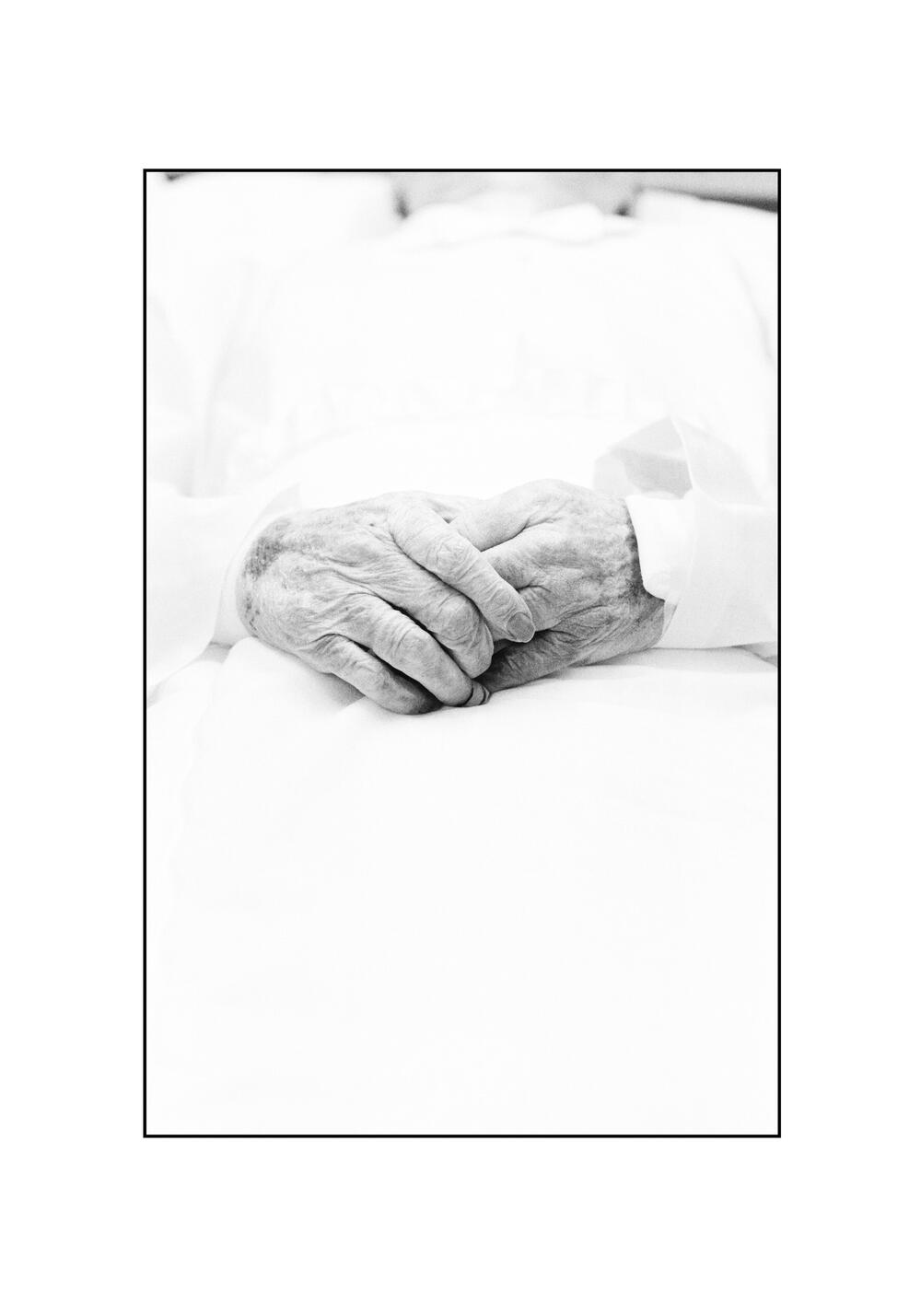

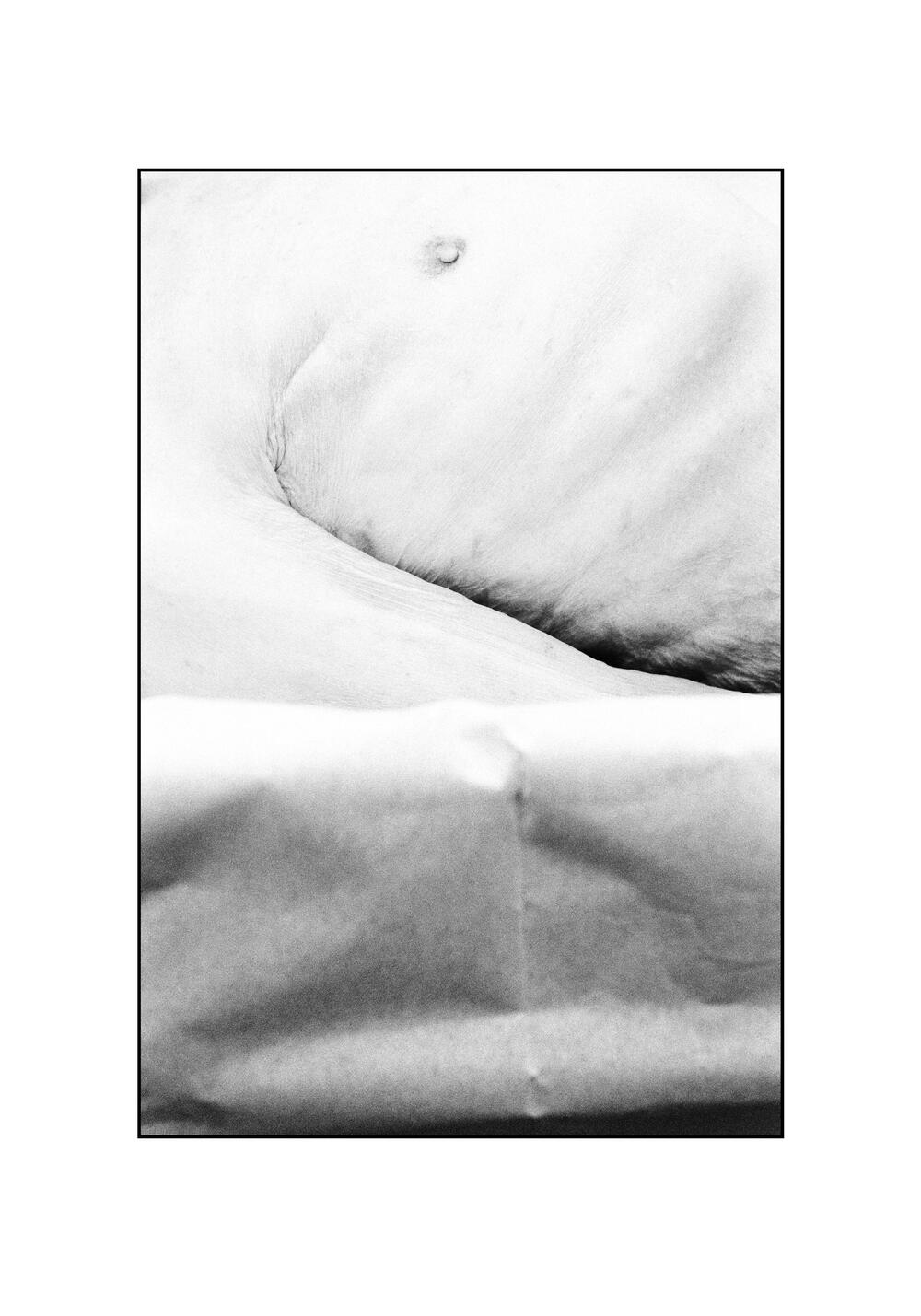

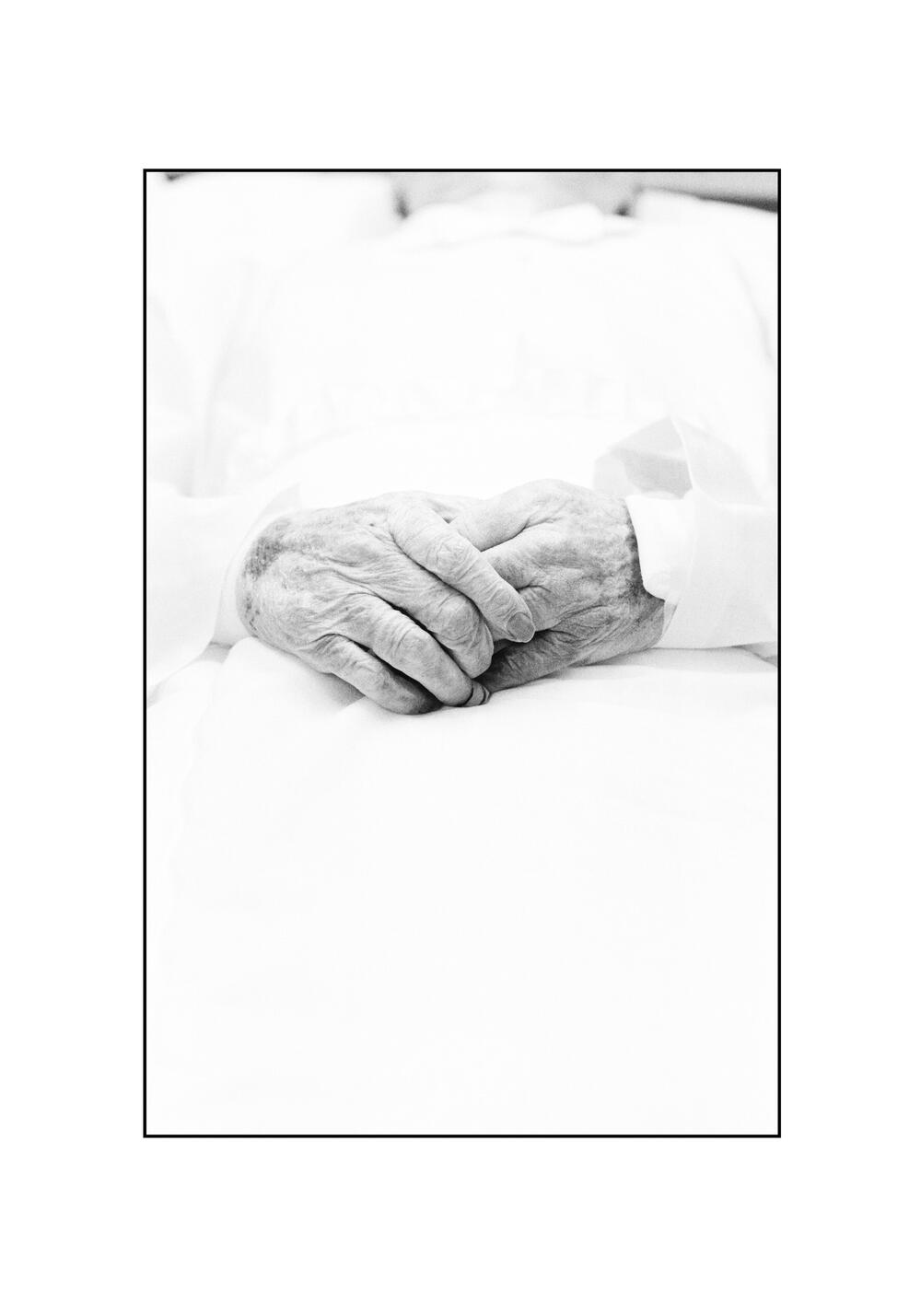

The flow of images and of remembrance — including the side branches already mentioned — irresistibly moves towards the sanctuary; the ‘Requiem’, however, with its three white, large-format photographs lit from behind, does not necessarily manifest the culmination of the photographic installation. Instead, the remarkable triptych marks the — undramatic — ending of a teleology that leads all viewers/visitors to these three interconnected images: a teleology that also defines their lives, whether or not they wish to admit it. The middle of the triptych is occupied by an almost completely white surface or — in the sense of Theodore Fontane — a problematic ‘field too wide’, which it is better not to contemplate. The motif is a white bed sheet. To the right and left, two vertical-format photographs — also in white — flank the central image. Fragments of a human figure emerge from their whiteness: two hands folded together and the right part of a torso. These are photographic images of death. The medium of photography, which causes life to freeze, is — doubly — sealed by death. The photographs communicate that which death has brought to an end to the memory of those who live on. Only in the memory of others do we live on after death. Schlote goes back to the anthropological source of all representations: the preservation of memories. ‘Requiem’ — the opening prayer provided the name for the practice referred to by this term: ‘Requiem aeternam dona eis, Domine’ or ‘Eternal rest grant unto them, O Lord’. In European culture, white represents the colour of light — the door is opening. In other cultures, it is the colour of mourning — and in these cultures, the door is opening as well. However, not all people see things from this point of view. Light is also capable of drying up all life.

Rarely has an artist more clearly presented the essence of all (not just photographic) images and explored their potential and their limits more intensively and imaginatively than Olaf Schlote. To put it briefly: a masterpiece.

Klaus Honnef